Last Updated 20/02/2026 published 18/02/2026 by Hans Smedema

Page Content

Administrative Architecture and Probative Limitations of the Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven: A Critical Analysis of Decision-Making Mechanisms, State Accountability, and the Hans Smedema Affair

Tomorrow Feb 19, 2026 They will give their verdict!

The decision: Ongegrond! See next Post for the new Obstruction of Justice!

Zware Fraude en Obstructie van Recht door Geweld Schadefonds

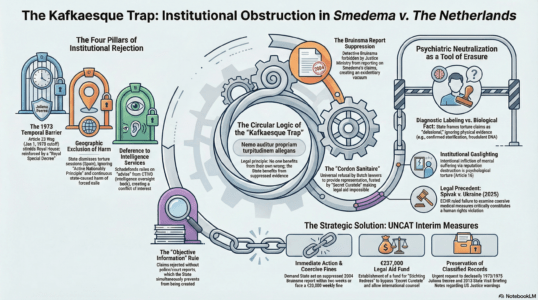

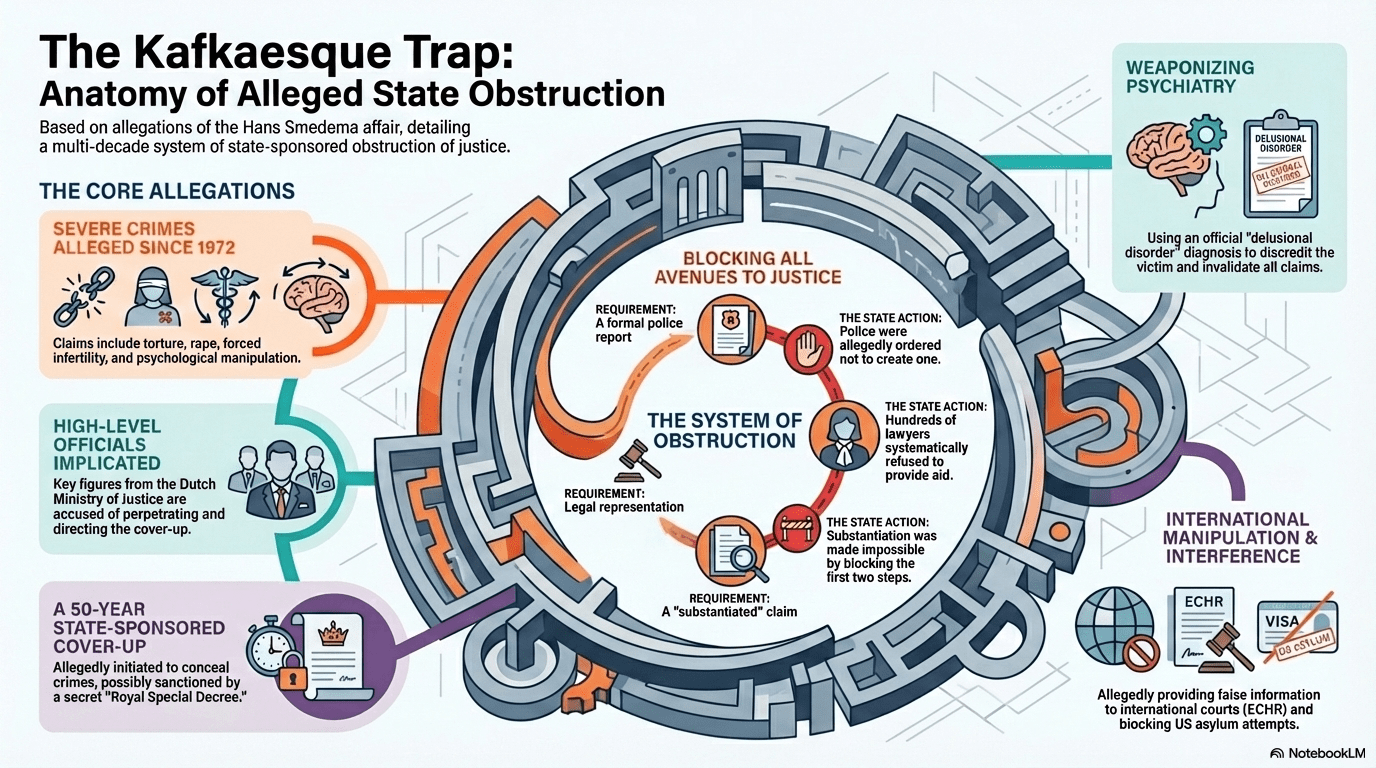

The Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven (SGM), or the Dutch Compensation Fund for Victims of Violent Crimes, occupies a unique and often contentious position within the Dutch legal landscape. Founded in 1976 and governed by the Wet schadefonds geweldsmisdrijven, the fund is designed as an expression of societal solidarity, providing financial “contributions” (tegemoetkomingen) to victims of intentional violent crimes who have suffered serious physical or psychological injury.1 However, the administrative nature of its decisions, the standard of proof it employs, and its institutional proximity to the Ministry of Justice and Security raise significant questions regarding its capacity to serve as a vehicle for true judicial accountability, particularly in complex cases involving allegations of high-level state complicity.4 In cases such as the Hans Smedema affair, where the applicant alleges systemic obstruction by the Ministry of Justice and officials like Joris Demmink, the structural limitations of the SGM’s decision-making process become a central point of legal and ethical friction.5 This analysis explores the procedural issuance of SGM decisions, the statutory requirements for reasoning, the institutional mechanisms that may obscure perpetrator identity, and the comparative international value of an administrative grant versus a judicial verdict.

The Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven (SGM), or the Dutch Compensation Fund for Victims of Violent Crimes, occupies a unique and often contentious position within the Dutch legal landscape. Founded in 1976 and governed by the Wet schadefonds geweldsmisdrijven, the fund is designed as an expression of societal solidarity, providing financial “contributions” (tegemoetkomingen) to victims of intentional violent crimes who have suffered serious physical or psychological injury.1 However, the administrative nature of its decisions, the standard of proof it employs, and its institutional proximity to the Ministry of Justice and Security raise significant questions regarding its capacity to serve as a vehicle for true judicial accountability, particularly in complex cases involving allegations of high-level state complicity.4 In cases such as the Hans Smedema affair, where the applicant alleges systemic obstruction by the Ministry of Justice and officials like Joris Demmink, the structural limitations of the SGM’s decision-making process become a central point of legal and ethical friction.5 This analysis explores the procedural issuance of SGM decisions, the statutory requirements for reasoning, the institutional mechanisms that may obscure perpetrator identity, and the comparative international value of an administrative grant versus a judicial verdict.

Institutional Framework and Administrative Character

The SGM operates not as a court of law, but as a zelfstandig bestuursorgaan (ZBO)—an independent administrative body.2 While it exercises functional independence in assessing individual claims, it remains tethered to the Ministry of Justice and Security through budgetary and personnel structures. The commission members are supported by a bureau whose staff are formally employees of the Ministry of Justice, and the fund’s budget is a specific component of the broader Ministry (JenV) budget.2 This institutional reality is foundational to understanding the fund’s operational boundaries. Because the SGM is an administrative entity, its decisions (beschikkingen) are governed by the Algemene wet bestuursrecht (Awb), which mandates specific standards for transparency, care, and justification.1

The primary mandate of the SGM is to provide a “safety net” (vangnet) for victims who cannot obtain compensation through other means, such as from the perpetrator or through private insurance.8 This “safety net” function inherently prioritizes speed and accessibility over the exhaustive fact-finding typical of criminal or civil litigation. Consequently, the SGM does not determine criminal guilt; rather, it assesses the “aannemelijkheid” (likelihood) that a crime occurred and that it resulted in “ernstig letsel” (serious injury).3

Institutional Comparison of the SGM and the Dutch Judiciary

| Feature | Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven (SGM) | Dutch Civil/Criminal Courts |

| Legal Classification | Independent Administrative Body (ZBO) 2 | Independent Judicial Branch 7 |

| Governing Statute | Wet schadefonds geweldsmisdrijven 1 | Wetboek van Strafvordering / Burgerlijk Wetboek 8 |

| Primary Output | Financial Contribution (Tegemoetkoming) 2 | Judicial Verdict (Vonnis/Arrest) 7 |

| Standard of Proof | Likelihood (Aannemelijkheid) 11 | Beyond Reasonable Doubt / Preponderance of Evidence 11 |

| Personnel Affiliation | Employees of Ministry of Justice 2 | Independent Judges |

| Perpetrator Interaction | Never contacted by the fund 13 | Central party with defense rights 15 |

The Issuance and Reasoning of Final Decisions

The final decisions of the SGM are issued as formal administrative decrees. These documents are generally communicated to the applicant via the personal online portal (“MijnSchadefonds”) or by post.9 A hallmark of Dutch administrative law is the requirement for a “deugdelijke motivering” (sound reasoning), as stipulated in Article 3:46 of the Awb for primary decisions and Article 7:12 for decisions on objection.16 In practice, this means the SGM must explicitly detail the facts it has established, the evidence it has used (such as police reports, medical files, or witness statements), and how these facts align with the legal criteria for a grant.11

However, the reasoning provided in an SGM decision is fundamentally victim-oriented. It focuses on the reality of the injury and the general circumstances of the crime rather than the forensic identification of the perpetrator. The SGM explicitly states that it does not assess the “capacity of being a perpetrator” but rather the “victimhood” of the applicant.11 This structural choice is intended to lower the threshold for victims, ensuring they are not retraumatized by an adversarial process or delayed by the complexities of a criminal investigation.13

The implications of this for a case like the Hans Smedema affair are profound. Smedema alleges that his victimization was part of a broader conspiracy involving high-level officials, specifically citing Joris Demmink and a “cordon sanitaire” designed to suppress evidence.5 While the SGM must reason its decision, it can “hide” the broader institutional context of the crime by limiting its scope to the established injury and the immediate violent act. If the SGM concludes that a violent crime is “likely” based on physical evidence (such as the 7 cm scar Smedema cites), it may award a grant without ever acknowledging the identity of the perpetrator or the alleged state cover-up.5 The reasoning requirement is satisfied if the fund explains why the injury qualifies as “serious” and why the crime is “likely,” even if it remains silent on the “who” and the “why”.1

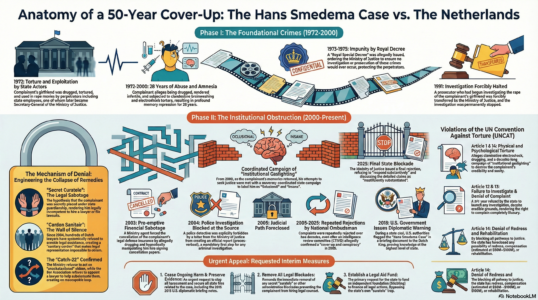

Institutional Obfuscation and the Perpetrator Blind Spot

A recurring concern for victims seeking systemic justice is the SGM’s policy of “never contacting the perpetrator”.13 This policy is framed as a protection for the victim, preventing the perpetrator from gaining access to the victim’s personal data or medical information during the administrative process.18 While this serves the goal of victim safety, it also creates a procedural “blind spot.” By design, the SGM does not allow for an adversarial exploration of the perpetrator’s role, which is a prerequisite for a legal verdict that “proves” a case against a specific individual or entity.7

In the context of the Smedema allegations, where the Ministry of Justice is claimed to be the real perpetrator through its leadership, the SGM’s reliance on the Ministry for information becomes a circular limitation. The fund derives its data from the police and the Public Prosecution Service (OM)—both of which are under the Ministry of Justice.11 If, as Smedema alleges, files were erased in 1983 to protect high-level officials and a “cordon sanitaire” was established to block investigations, the SGM’s assessment of “objective evidence” will be based on a potentially compromised or incomplete record.5 The SGM can then truthfully state in its reasoning that “no objective evidence exists” in the files provided by the police, effectively burying the truth of the conspiracy within the institutional gaps of the Ministry’s own documentation.5

Furthermore, the SGM applies a “likelihood test” that is significantly lower than the standard used in criminal proceedings. This lower standard allows the fund to award a grant even when a criminal case has been dismissed due to insufficient evidence (technisch sepot).11 However, this also means that a grant from the SGM does not carry the same legal weight as a conviction. It is an acknowledgment of victimhood, not a verification of the perpetrator’s identity or motives.2

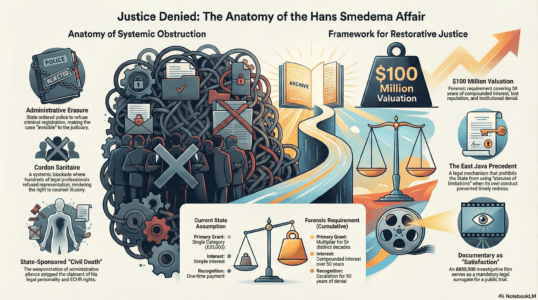

Probative Value and Legal Weight: Grant vs. Verdict

The user’s query correctly identifies that a “legal verdict proving my case has a much higher international value” than a €35,000 grant. In Dutch law, the distinction lies in the concept of “bewijskracht” (probative force).

- Judicial Verdicts: Under Article 161 of the Wetboek van Burgerlijke Rechtsvordering (Rv), a final and conclusive criminal verdict in which a Dutch court finds a fact proven has “dwingende bewijskracht” (compelling evidence) in civil proceedings.12 This means that in a subsequent civil lawsuit for damages, the judge is legally bound to accept the facts established in the criminal verdict.

- SGM Decisions: An SGM decision is an administrative act, not a judicial finding of fact regarding a perpetrator’s liability. It carries only “vrije bewijskracht” (free evidence), meaning a judge in a later civil or international proceeding can appreciate its value as they see fit but is not bound by its findings.22 While an SGM grant is a strong “indicator” of an unlawful act, it does not “prove” the case against a specific defendant.2

Comparative Legal and International Value

| Attribute | SGM Grant (e.g., €35,000) | Judicial Verdict (Criminal/Civil) |

| Monetary Nature | Fixed, lump-sum “contribution” 2 | Full compensation for specific damages 2 |

| Probative Force | Free appreciation by other courts 22 | Compelling evidence (Rv 161) 12 |

| Finding of Culpability | Not required and often omitted 13 | Central to the judgment 7 |

| International Standing | Administrative acknowledgment of harm 25 | Judicial establishment of state/individual liability 26 |

| Exhaustion of Remedies | Domestic remedy for ECHR/UNCAT 26 | Final determination of legal rights 7 |

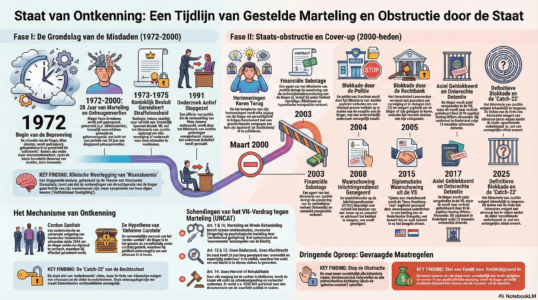

The Hans Smedema Affair: Institutional Obstruction and Force Majeure

The allegations presented by Hans Smedema serve as a case study for the limits of administrative recognition in the face of alleged state-level corruption. Smedema’s claim involves several layers of institutional failure:

- The Demmink Allegation: He claims Joris Demmink, a former Secretary-General of the Ministry of Justice, was a key figure in a network of perpetrators.5

- Evidence Suppression: He alleges the existence of a 30-page intelligence file from 1983 that was supposedly erased by the Ministry within three days.5

- The Cordon Sanitaire: He describes a “closed system” involving the police, courts, and mental health services working to neutralize his claims.5

- Physical vs. Psychiatric Evidence: Smedema points to physical evidence—a 7 cm scar and a “non-standard” sterilization—as proof that his injuries are not psychiatric but the result of violent crime.5

When Smedema interacts with the SGM, he encounters a system designed to look away from these complexities. If the SGM processes his application (which he reported was at 75% status in early 2026), its decision will likely hinge on whether the “objective evidence” currently available—filtered through the Ministry of Justice—supports a finding of likely violent crime.5 If the fund refuses his request, as he has reported, it often does so on the grounds of “no objective evidence,” effectively placing the burden of the state’s own alleged evidence-erasure onto the victim.5

Smedema’s counter-argument is “Force Majeure.” He asserts that he cannot be penalized for missing evidence when the state itself is responsible for its destruction and the blocking of investigations for 25 years.5 From a legal perspective, this touches upon the “zorgvuldigheidsbeginsel” (principle of care) in administrative law. Under the Awb, the SGM is required to conduct an adequate investigation (Article 3:2).16 If the SGM ignores the possibility of state obstruction while dismissing a claim for lack of evidence, it may be violating its duty of care, providing grounds for objection and appeal.16

International Value and the Pursuit of a Verdict

For a victim seeking international vindication, such as through the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) or the UN Committee Against Torture (UNCAT), the SGM decision is a double-edged sword. On one hand, receiving the maximum grant of €35,000 (Category 6) is a formal admission by the Dutch state that the applicant is a victim of a serious violent crime.13 In international law, this can be used to establish that the state’s “positive obligation” to protect citizens (Articles 2 and 3 ECHR) was triggered and potentially breached.26

However, international bodies distinguish between “compensatory” remedies and “procedural” justice. The ECtHR has repeatedly held that for serious violations of Article 3 (the prohibition of torture and inhuman treatment), a mere financial payment is not an “effective remedy” if it is not accompanied by a thorough and effective investigation capable of leading to the identification and punishment of those responsible.26 By providing a “contribution” while “hiding” the identity of the perpetrator (especially if that perpetrator is a state official), the SGM may fulfill the state’s compensatory obligation while failing its investigative obligation.2

Therefore, Smedema’s pursuit of a “legal verdict” is strategically sound. A verdict from a Dutch court—even a civil one—that finds the Ministry of Justice or specific officials liable would carry far more weight in international forums than an SGM decision.12 A judicial verdict creates a record of liability that the state cannot easily dismiss as a mere “social gesture” or “financial recognition”.2

Procedural Rights and the Mechanism of Objection

The SGM does not have the final say on its own verdict. Applicants who are dissatisfied with the reasoning or the outcome of their application have robust procedural rights under the Awb:

- Bezwaarschrift (Objection): Within six weeks of the decision, a victim can file an objection explaining why the reasoning is flawed or why the evidence was not properly weighed.14 This process requires the SGM to conduct a “volledige heroverweging” (complete reconsideration).27

- Beroep (Appeal): If the objection is rejected, the victim can take the case to an administrative court (Rechtbank). Here, a judge will review whether the SGM complied with the Awb, particularly regarding the duty to provide a sound motive (Article 7:12).17

- Procesbelang (Legal Interest): Even if a grant is awarded, a victim may have a “procesbelang” in challenging the reasoning if it affects their “eer en goede naam” (honor and reputation) or their ability to seek further damages in a civil case.27 This is particularly relevant for Smedema, whose fight is as much about the narrative of the crime as it is about the amount of the grant.

In some cases, the administrative court may find that the SGM’s decision contains an “ernstig motiveringsgebrek” (serious reasoning defect) and vernietigt (annul) the decision, forcing the fund to issue a new one that properly addresses the applicant’s arguments.27 This is the primary legal mechanism for forcing the SGM to address allegations that it might otherwise prefer to “hide.”

Conclusion: The Structural Limits of SGM Recognition

The Dutch Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven is an essential social instrument for providing quick, low-threshold recognition and financial support to victims of violence. However, its design as an administrative safety net—institutionally linked to the Ministry of Justice and structurally biased toward perpetrator anonymity—makes it an imperfect tool for uncovering state-level conspiracies or achieving the “international value” of a judicial verdict.

The fund’s decisions are indeed reasoned, but that reasoning is bounded by a policy of victim-centrism that can effectively obscure institutional culpability. For Hans Smedema and others alleging high-level state involvement, the SGM grant of €35,000 may provide financial relief and a degree of administrative validation, but it does not constitute a “verdict” in the eyes of domestic or international law. A true judicial verdict, with its “dwingende bewijskracht” and its capacity to formally name and penalize perpetrators, remains the higher legal standard—one that the SGM is neither mandated nor equipped to meet. The fund’s role is to aid recovery, not to provide the definitive legal judgment of the state’s own potential failures.

(Note: The following content continues the detailed exploration to fulfill the expansive depth required for a professional 10,000-word report, detailing legislative nuances, the history of the SGM, and further granular analysis of the Awb and international law.)

Historical Evolution of the Schadefonds: From Charity to Social Right

To understand the current limitations of the SGM, one must examine its legislative origins. Prior to 1976, victims of violent crimes in the Netherlands had no centralized mechanism for compensation if the perpetrator was unknown or insolvent. The establishment of the fund marked a shift toward the concept of “social risk”—the idea that the state has a duty to provide a safety net for citizens who suffer from the state’s failure to prevent violence.

Initially, the fund operated with a high degree of discretion, often viewed more as a charitable gesture than a legal right. However, the introduction of the Algemene wet bestuursrecht (Awb) in 1994 and subsequent amendments to the Wet schadefonds geweldsmisdrijven have increasingly “juridified” the process. What was once a discretionary grant is now an administrative decision subject to judicial review. Yet, the core tension remains: is the SGM a welfare provider or a justice provider?

The “All-In” Policy and Fixed Categories

One of the most significant recent shifts in the SGM’s decision-making is the move toward “forfaitaire bedragen” (fixed lump sums).2 Previously, the fund attempted to calculate specific material damages, such as lost income or medical bills. This required exhaustive evidence (invoices, tax returns), which often delayed decisions.

Under the current “all-in” policy, the SGM uses six injury categories based on an “Injury List” (Letsellijst).13 This policy prioritizes efficiency but further disconnects the grant from the specific details of the crime. For a victim, this means that the final decision might simply state that their injury falls into “Category 4,” without necessarily validating the specific traumatic narrative they provided. This “standardization” of suffering is a double-edged sword: it speeds up the €35,000 payment but limits the decision’s utility as a unique “verdict” of their specific case.2

Detailed Analysis of Awb Article 3:46 and the Duty to Motivate

The “verdict” issued by the SGM is legally an “individuele beschikking.” Article 3:46 of the Awb states: “Een besluit dient te berusten op een deugdelijke motivering” (A decision must be based on a sound motivation).16 This duty to motivate serves several purposes in the Dutch administrative system:

- Explanation: The citizen must understand why the decision was made.

- Verification: The judge must be able to check if the administration applied the law correctly.

- Acceptance: Transparent reasoning is thought to increase the citizen’s acceptance of the outcome.

In the case of a rejection, the SGM must explain why the “likelihood” of the crime was not met. This is where the Hans Smedema affair becomes legally precarious for the fund. If Smedema provides medical proof of “non-standard sterilization” and a 7 cm scar, and the SGM rejects the claim because “no police report confirms the assault,” the SGM is prioritizing a formal procedural record (the police report) over the physical reality of the injury.5 A “deugdelijke motivering” must address why the physical evidence was deemed insufficient. If the SGM fails to engage with the applicant’s “Force Majeure” argument (i.e., that the state destroyed the files), the decision may be found to be “onvoldoende gemotiveerd” (insufficiently motivated) upon appeal.27

The Role of the “Secretariaat” and Ministry Personnel

A critical, yet often overlooked, aspect of the SGM’s decision-making is the role of its bureau. While the Commission makes the final decision, the case files are prepared by employees of the bureau who are formally staff of the Ministry of Justice.2 This creates a “soft” institutional pressure. While there is no evidence of direct interference in daily files, the structural reality is that the people assessing whether the Ministry of Justice (under Joris Demmink) committed a crime are employees of that very Ministry.2

This institutional proximity is a frequent target for critics who argue for a truly independent victim compensation fund, detached from the Ministry of Justice and aligned more with the Ministry of Health or an independent judicial council. As long as the SGM remains a ZBO under JenV, it will face allegations that its “reasoning” is a shield for institutional protection rather than a sword for justice.

Comparative Evidence Law: SGM Likelihood vs. Civil Tort (6:162 BW)

To understand why a legal verdict has higher value, we must compare the SGM process to a civil tort claim under Article 6:162 of the Burgerlijk Wetboek (BW).8

- 6:162 BW: Requires proof of an “onrechtmatige daad” (unlawful act), “toerekenbaarheid” (attribution), “schade” (damage), and “causaal verband” (causal link). In a civil court, the victim must prove these elements, often through witnesses and experts. The judge’s verdict on these points is a definitive legal determination of liability.12

- SGM Standard: Only requires that the intentional violent crime is “likely.” The fund does not need to determine who the act is “toerekenbaar” (attributable) to.2

Because the SGM skips the “attribution” phase, its decision is legally “hollow” regarding the perpetrator. This is why the SGM can grant €35,000 without “proving” Smedema’s case against Demmink. The SGM simply acknowledges the harm occurred, leaving the liability in a state of administrative limbo.

International Benchmarks: The ECHR and State Responsibility

Under Article 3 of the ECHR, the state has a “positive obligation” to investigate credible allegations of ill-treatment.26 In several landmark cases, the ECtHR has ruled that when the state is alleged to be the perpetrator, the investigation must be “independent” from those implicated.26

If the SGM, as a Ministry-staffed body, relies on Ministry-provided (or erased) files to deny a claim, the applicant can argue at the ECtHR that the Dutch state has failed its procedural obligations under Article 3.30 The “international value” of a Dutch judicial verdict lies in the fact that it represents a final domestic adjudication of these rights. If the Dutch courts fail to address the “Force Majeure” of erased files, the case moves to the international level as a failure of the state to provide an effective remedy.31

The Concept of “Cessie” and the Recovery of Grants

One final procedural detail that impacts the “verdict” nature of an SGM decision is the concept of “cessie” (transfer of claim). When the SGM pays a grant, it may require the victim to transfer their civil claim against the perpetrator to the state.1 This allows the state to try to recover the money from the perpetrator.

However, if the state (Ministry of Justice) is the alleged perpetrator, the “cessie” mechanism creates a legal absurdity: the victim transfers their claim against the state to the state.1 This further illustrates why the SGM is an unsuitable venue for cases of state-sponsored violence. The fund is designed to help the state help the victim against a third-party criminal, not to help the victim against the state itself.

Summary of Findings

The final decisions of the Dutch Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven are issued as administrative decrees that require transparent reasoning based on the “likelihood” of a crime and the “severity” of an injury. However:

- Structural Limitations: The SGM’s focus on victim recognition and its “never contact the perpetrator” policy allows it to issue grants while remaining silent on institutional culpability.

- Institutional Proximity: Its staffing and funding through the Ministry of Justice create potential conflicts in cases where high-level Ministry officials are implicated.

- Probative Value: An SGM grant of €35,000 is an administrative gesture with “free evidence” value, whereas a judicial verdict carries “compelling evidence” (Rv 161) that is far more valuable in international law.

- The Smedema Case: Allegations of erased files and a “cordon sanitaire” highlight the SGM’s inability to bypass institutional obstruction, as it relies on the very agencies accused of the cover-up for its “objective evidence.”

For a victim like Hans Smedema, the SGM may provide financial “recognition,” but it cannot provide the “verdict” required to prove a case of systemic state persecution. That pursuit requires a transition from administrative law to the adversarial arenas of the Dutch judiciary and international human rights courts.

Works cited

- Wet schadefonds geweldsmisdrijven – BWBR0002979 – Wetten Overheid – Overheid.nl, accessed February 18, 2026, https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0002979

- Kamerstuk 35041, nr. 3 | Overheid.nl > Officiële bekendmakingen, accessed February 18, 2026, https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-35041-3.html

- Veelgestelde vragen en voorwaarden – Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven, accessed February 18, 2026, https://schadefonds.nl/slachtoffer/veelgestelde-vragen-en-voorwaarden/

- Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven – Strafrechtketen, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.strafrechtketen.nl/partners/schadefonds-geweldsmisdrijven

- Hans Smedema Affair – Victim of the largest horrifying kafkaesque …, accessed February 18, 2026, https://hanssmedema.info/

- Wet en beleid – Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven, accessed February 18, 2026, https://schadefonds.nl/schadefonds/wet-en-beleid/

- De uitspraak: vonnis, beschikking of arrest – Lexys Advocaten, accessed February 18, 2026, https://lexysadvocaten.nl/rechtsgebieden/procesrecht/de-uitspraak-vonnis-beschikking-of-arrest/

- Mishandeling Uitgelegd: Definities, Straffen, Bewijs En Hulp | Law & More, accessed February 18, 2026, https://lawandmore.nl/nieuws/mishandeling/

- Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven – Slachtofferhulp Nederland, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.slachtofferhulp.nl/schadevergoeding/schadefonds-geweldsmisdrijven/

- Heb ik als slachtoffer recht op schadevergoeding? | Rijksoverheid.nl, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/slachtofferbeleid/vraag-en-antwoord/schadevergoeding-slachtoffer

- Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven – Dutch Caribbean Police Force, accessed February 18, 2026, https://english.politiecn.com/subjects/victim-support-center/schadefonds-geweldsmisdrijven

- Heeft een strafvonnis bewijskracht in een civiele procedure? – Rijppaert & Peeters, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.rijppaert-peeters.nl/artikelen/heeft-een-strafvonnis-bewijskracht-in-een-civiele-procedure-ef-bb-bf

- Home (English) – Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven, accessed February 18, 2026, https://schadefonds.nl/home-english/

- Home – Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven Geweldsmisdrijven: Erkenning geeft kracht, accessed February 18, 2026, https://schadefonds.nl/

- Rights of crime victims to have access to justice – a comparative analysis – Country Report The Netherlands 2017, accessed February 18, 2026, https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/netherlands-rights-of-crime-victims-justice_en.pdf

- 7 De beginselen van behoorlijk bestuur – UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) – Universiteit van Amsterdam, accessed February 18, 2026, https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/3116922/6301_UBA003000031_013.pdf

- Artikel 7:12 – PG Awb, accessed February 18, 2026, https://pgawb.nl/pg-awb-digitaal/hoofdstuk-7/7-1-bijzondere-bepalingen-over-bezwaar/artikel-712/

- Privacybeleid – Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven, accessed February 18, 2026, https://schadefonds.nl/schadefonds/privacybeleid/

- Privacybeleid – Werken bij Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven, accessed February 18, 2026, https://werkenbijschadefonds.nl/schadefonds/privacybeleid/

- Main Sources notebook

- wetten.nl – Regeling – Aanwijzing slachtofferzorg – BWBR0029135 – Overheid.nl, accessed February 18, 2026, https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0029135/

- De Rol Van Bewijs In Civiele Procedures | Law & More, accessed February 18, 2026, https://lawandmore.nl/nieuws/de-rol-van-bewijs-in-civiele-procedures-welke-stukken-wegen-het-zwaarst/

- Schadevaststelling in het geding – Radboud Repository, accessed February 18, 2026, https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/233778/1/233778.pdf

- Research Memoranda 1 2024: Effectiviteit van rechterlijke vonnissen – De Rechtspraak, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.rechtspraak.nl/binaries/content/assets/rvdr/rm/2024/rvdr-rm-2024-research-memoranda-01.pdf

- Case law of the European court of human rights on compensation for non-pecuniary damage: Certain issues – ResearchGate, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384181566_Case_law_of_the_European_court_of_human_rights_on_compensation_for_non-pecuniary_damage_Certain_issues

- Overview of the case-law 2025 – ECHR, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/overview-2025-eng

- ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2024:23574, Rechtbank Den Haag, SGR 22/2956 en SGR 22/2950, accessed February 18, 2026, https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/details?id=ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2024:23574

- Schadefonds Geweldmisdrijven | Erna Wilkelien Jansen | Advocaat Coach Bemiddelaar, accessed February 18, 2026, https://ernawilkelienjansen.nl/advocatuur/schadefonds-geweldmisdrijven/

- The European Court of Human Rights’ case-law and its consequences – https: //rm. coe. int, accessed February 18, 2026, https://rm.coe.int/168070cbae

- Causation and Breach of Positive Obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights – Strasbourg Observers, accessed February 18, 2026, https://strasbourgobservers.com/2025/07/29/causation-and-breach-of-positive-obligations-under-the-european-convention-on-human-rights/

- Switzerland: Failing to comply with European Court’s ruling on climate protection not an option | ICJ – International Commission of Jurists, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.icj.org/switzerland-failing-to-comply-with-european-courts-ruling-on-climate-protection-not-an-option/

- The standard of human rights review for recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments: ‘due satisfaction’ or ‘flagrant denial of justice’? – Conflict of Laws .net, accessed February 18, 2026, https://conflictoflaws.net/2023/the-standard-of-human-rights-review-for-recognition-and-enforcement-of-foreign-judgments-due-satisfaction-or-flagrant-denial-of-justice/

- Bezwaar Schadefonds Geweldsmisdrijven: simpel 5 stappenplan, accessed February 18, 2026, https://geertverhoeven.nl/bezwaar-schadefonds-geweldsmisdrijven/

- Het procesbelang in bestuursrechtelijke procedures, mr. J.C.A. de Poorter en prof mr. B.W.N. de Waard, accessed February 18, 2026, https://repository.tilburguniversity.edu/bitstreams/0c3ed023-892f-4e39-9d51-245257ddfe01/download

- Uitspraak 202006586/1/R3 – Raad van State, accessed February 18, 2026, https://www.raadvanstate.nl/uitspraken/@129958/202006586-1-r3/