Last Updated 04/02/2026 published 04/02/2026 by Hans Smedema

Page Content

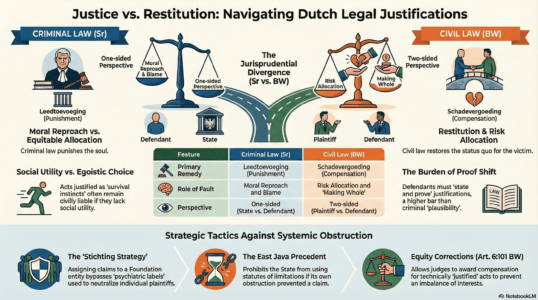

Comparative Analysis: Criminal Justifications and Civil Liability in Dutch Law

Google NotebookLM Plus Infographic and Report:

1. The Jurisprudential Intersection: Criminal Influence on Civil Justifications

In the Dutch legal tradition, the demarcation between criminal and civil law is a fundamental tenet, yet the conceptualization of justifications—grounds that negate the “unlawful” character of an act—reveals a deep-seated strategic interdependence. Understanding how criminal law concepts have permeated the Dutch Civil Code (Burgerlijk Wetboek or BW) is essential for high-level synthesis; while these domains are functionally separate, their jurisprudential DNA regarding justifications is profoundly intertwined. The civil approach to an “unlawful act” (onrechtmatige daad) under Article 6:162 BW is historically and conceptually tethered to the justifications codified in the Penal Code (Wetboek van Strafrecht or Sr).

As M.E. Franke (2022) demonstrates, the civil discourse on justifications has largely been an exercise in adopting criminal law frameworks. When an act meets the threshold of a tort, it may lose its unlawful character if a justification is established. These grounds are primarily synthesized into three groups derived from Articles 40–44 Sr:

The Triad of Statutory Justifications

- Legal Duty and Official Orders: Acts performed under a statutory provision (wettelijk voorschrift) or an authorized official order (ambtelijk bevel). Franke notes that while this is conceptually straight from the Penal Code, the transition into the civil domain requires an assessment of whether the duty was exercised within the bounds of its intended social purpose.

- Force Majeure and Necessity (Overmacht): A conflict of duties or external pressure where the actor chooses between two competing interests. In the civil domain, this often translates into the “lesser of two evils” doctrine.

- Self-Defense (Noodweer): The necessary defense of person or property against an immediate, unlawful assault.

This conceptual dependence creates a paradox: while nearly every civil manual begins by citing the Penal Code, the underlying systemic goals of the two domains are in a state of perpetual conflict—the criminal pursuit of moral retribution versus the civil mandate for financial restitution.

——————————————————————————–

2. Divergent Objectives: Retribution vs. Restitution

The application of a justification is dictated by the governing telos of the legal system in which it is invoked. Criminal law is fundamentally “moralizing,” seeking to determine if an individual deserves reproach and a subsequent “leedtoevoeging” (infliction of pain). Civil law, by contrast, is often “amoral” and risk-oriented; its primary concern is not the soul of the actor, but the equitable allocation of loss and the restoration of the status quo.

A criminal judge may find an act morally excusable, but a civil judge must determine who should bear the burden of the damage. A “moral excuse” that removes criminal guilt does not automatically transfer the financial risk from the actor to the innocent victim.

Comparative Objectives: Sr vs. BW

| Feature | Criminal Law (Sr) | Civil Law (BW) |

| Protected Interests | Public Order and General Interest | Private Interests and Personal Rights |

| Primary Remedy | Leedtoevoeging (Punishment) | Schadevergoeding (Compensation) |

| Role of Fault | Moral Reproach and Blame | Risk Allocation and “Making Whole” |

| Perspective | One-sided / Inquisitorial (State vs. Defendant) | Two-sided / Accusatorial (Plaintiff vs. Defendant) |

The “So What?” factor for practitioners is profound: a justification in criminal law removes the “crime” because the state no longer seeks retribution for a socially neutral act. In civil law, however, the removal of “unlawfulness” is often a threshold that merely redirects the inquiry toward risk-based liability or equity corrections. In a two-sided assessment, an actor who makes an egoistic choice may be cleared of moral blame but remains the logical party to bear the cost of that choice.

——————————————————————————–

3. Procedural Mechanics and the Burden of Proof

The “battle of justifications” undergoes a radical transformation when moving from the inquisitorial setting of a criminal trial to the accusatorial framework of civil litigation. These procedural hurdles frequently result in “Divergent Verdicts” based on the same set of facts.

The Shift in Proof In criminal proceedings, the defendant only needs to make a justification “plausible” (aannemelijk). If the defendant presents facts suggesting noodweer, the Public Prosecutor bears the burden of disproving it. In civil litigation, the burden is far more demanding. Under the standard rules of evidence, the defendant has the full burden to “state and prove” (stellen en bewijzen) the facts underlying a justification. Failure to meet this rigorous evidentiary threshold means the act remains “unlawful” (onrechtmatig), even if a criminal court acquitted the party.

The Two-Sided Assessment and Equity Corrections Unlike the one-sided criminal prosecution, the civil judge performs a sophisticated balance of interests (belangen afwegen). This includes the degree of caution expected from the plaintiff and the relative weight of the interests at stake. Crucially, the civil judge can apply a “billijkheidscorrectie” (equity correction) under Article 6:101 BW. This allows the court to adjust the liability based on the “seriousness of the norm violation” and the degree of reproach, ensuring that even a technically justified act does not leave an innocent victim entirely uncompensated due to an imbalance in the parties’ relative positions.

——————————————————————————–

4. Criminal Concepts in a Civil Tort Context: Force Majeure and Self-Defense

The practical application of Noodweer and Overmacht within the framework of Article 6:162 BW requires a distinction often overlooked by generalists: the “maatschappelijk nuttige” (socially useful) versus the “maatschappelijk neutrale” (socially neutral) act.

In the classic “Plank of Carneades” (Vlot van Karneades) scenario, where one survivor pushes another off a one-person plank, criminal law justifies the act as a survival instinct—a socially neutral, “egoistic choice” that does not warrant prison. However, civil law views this as a risk-allocation event. Because the act was not “socially useful” (unlike, for instance, a doctor performing emergency surgery that causes minor injury), the actor who preserved their own interest at the expense of another’s life remains civilly liable for the damage.

Conditions for Civil Justification

- Proportionality: The harm inflicted must not be out of proportion to the interest protected. Civil courts apply a stricter threshold, focusing on the victim’s right to integrity.

- Subsidiarity: The defendant must prove no less harmful alternatives existed.

- Culpa in Causa: A justification will fail if the defendant’s own prior negligence created the emergency. If the actor is “at fault for the cause,” the civil court will not allow the justification to block a claim.

- Social Utility: The court distinguishes between acts that benefit society (e.g., firefighting damage) and purely “neutral” egoistic preservation.

——————————————————————————–

5. The Residual Liability: Life Beyond “Unlawfulness”

In Dutch law, the removal of “unlawfulness” (onrechtmatigheid) does not terminate the possibility of a compensation claim. A party can be technically justified yet still trigger liability through “other grounds,” such as risk-based liability or the principle of redelijkheid en billijkheid (reasonableness and fairness).

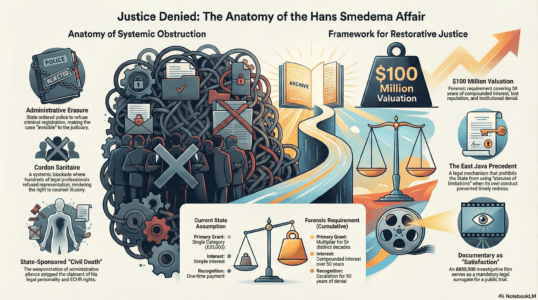

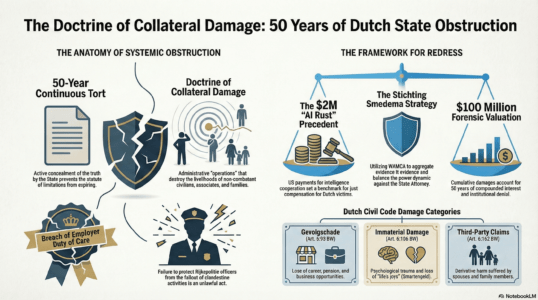

The East Java Precedent and Administrative Obstruction Strategic practitioners must look to the “East Java Precedent” when dealing with state-sponsored obstruction. While the State often attempts to hide behind technical justifications or the statute of limitations (verjaring), this precedent establishes that the State cannot invoke a statute of limitations if its own conduct—a “paper trail of obstruction”—prevented the victim from filing a claim. This is a vital tool for bypassing procedural time-bars created by institutional gaslighting or administrative silence.

Strategic Takeaways for Legal Practitioners

- The “Stichting Strategy”: When a claimant is neutralized by a psychiatric label (e.g., “delusional disorder”), the most effective tactical countermeasure is the assignment of the claim to a legal entity (Foundation). A legal person cannot be diagnosed with a psychiatric illness, effectively bypassing the “psychiatric veto” and forcing the court to adjudicate the facts of the tort rather than the mental state of the plaintiff.

- Acquittal \neq Immunity: A criminal acquittal is a moral judgment; it does not constitute a civil shield.

- Forensic Fact-Verification: Never rely on administrative or psychiatric labels. In civil litigation, the “Two-Sided” nature of the assessment allows for a deeper forensic dive into the reality of the harm, regardless of state “justifications.”

——————————————————————————–

6. Synthesis and Final Conclusion

The interplay between criminal justifications and civil liability reveals a deep systemic tension in the Dutch legal order. A justification is a specialized tool for “altering the judgment” of an act, yet its power is strictly confined by the domain in which it is used. Criminal law prevents the state from unjustly punishing an individual; civil law ensures that the costs of human action are placed on the shoulders of those responsible for the risk.

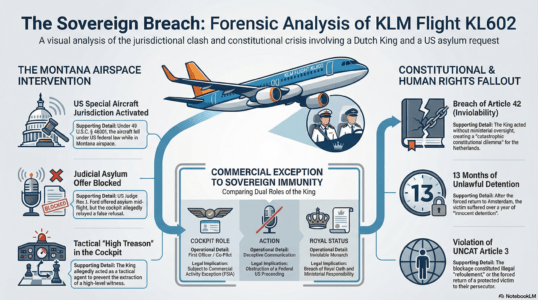

However, a “Systemic Blindness” occurs when these domains are conflated, particularly within the current administrative structure of the Ministry of Justice and Security (JenV). The amalgamation of the police (Security) and the law (Justice) into a single “Moloch” has eroded the checks and balances necessary for legal protection. This “Leviathan” structure allows for a “Civil Death” mechanism, where a citizen alleging state-sponsored crime is neutralized via “Administrative Flagging” or the weaponization of psychiatry.

The “Onno van der Hart Paradox”—where a clinical schism between “Structural Dissociation” (trauma model) and “Schizophrenia” (biomedical model) is used to delegitimize a victim—illustrates how a medical misdiagnosis can function as a de facto legal verdict. When the state accepts a “delusional” label without forensic verification of the underlying facts, it incentivizes institutional gaslighting over the rule of law.

Ultimately, Dutch jurisprudence maintains its integrity only when it refuses this conflation. Legal practitioners must look past the “secret curatele” of administrative labeling and utilize tactical maneuvers like the “Stichting strategy” and the “East Java” principles to ensure that the civil court remains a venue for truth-finding and restitution, rather than a rubber stamp for state-sponsored justifications.