Last Updated 19/01/2026 published 02/01/2026 by Hans Smedema

Page Content

The Leviathan of the Low Countries: Anatomy of a Constitutional Crisis and the Imperative for Administrative Partition of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security

‘Life is not measured by the moments we breathe, but by the moments that take our Breath away!’

Executive Summary: The Crisis of the Mega-Department

The governance of justice and security in the Netherlands confronts a profound crisis of legitimacy and functionality. Since the administrative amalgamation of 2010, which fused the classical Ministry of Justice with the public order and safety portfolios of the Ministry of the Interior to create the Ministry of Security and Justice (later renamed Justice and Security, JenV), the Dutch state has operated under the aegis of a “super-ministry.” This institutional design, initially championed under the banner of New Public Management efficiency and a decisive, unified combat against crime, has metastasized into a “Moloch”—an ungovernable bureaucratic behemoth that structurally conflates the distinct constitutional functions of legal protection (rechtsbescherming) and law enforcement (rechtshandhaving).

This report posits that the current architectural configuration of JenV represents a fundamental threat to the Dutch democratic legal order. By housing the Public Prosecution Service (OM), the National Police, the intelligence services (AIVD/NCTV), the prison service (DJI), and the judiciary’s administrative support under a single political roof, the system has eroded the internal checks and balances necessary to prevent executive overreach. The result is a “security state” logic that frequently overrides the principles of the “constitutional state” (rechtsstaat). The Minister, burdened by an unmanageable span of control, is forced into a reactive, incident-driven mode of governance where strategic oversight is sacrificed for political damage control, and where the preservation of the bureaucracy takes precedence over the rectification of injustice.

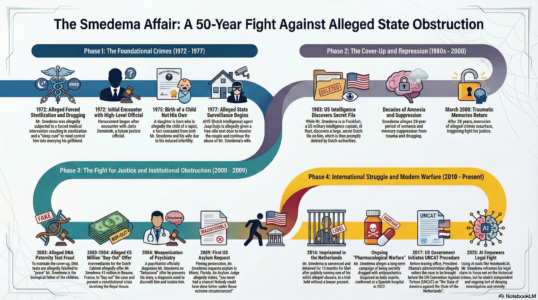

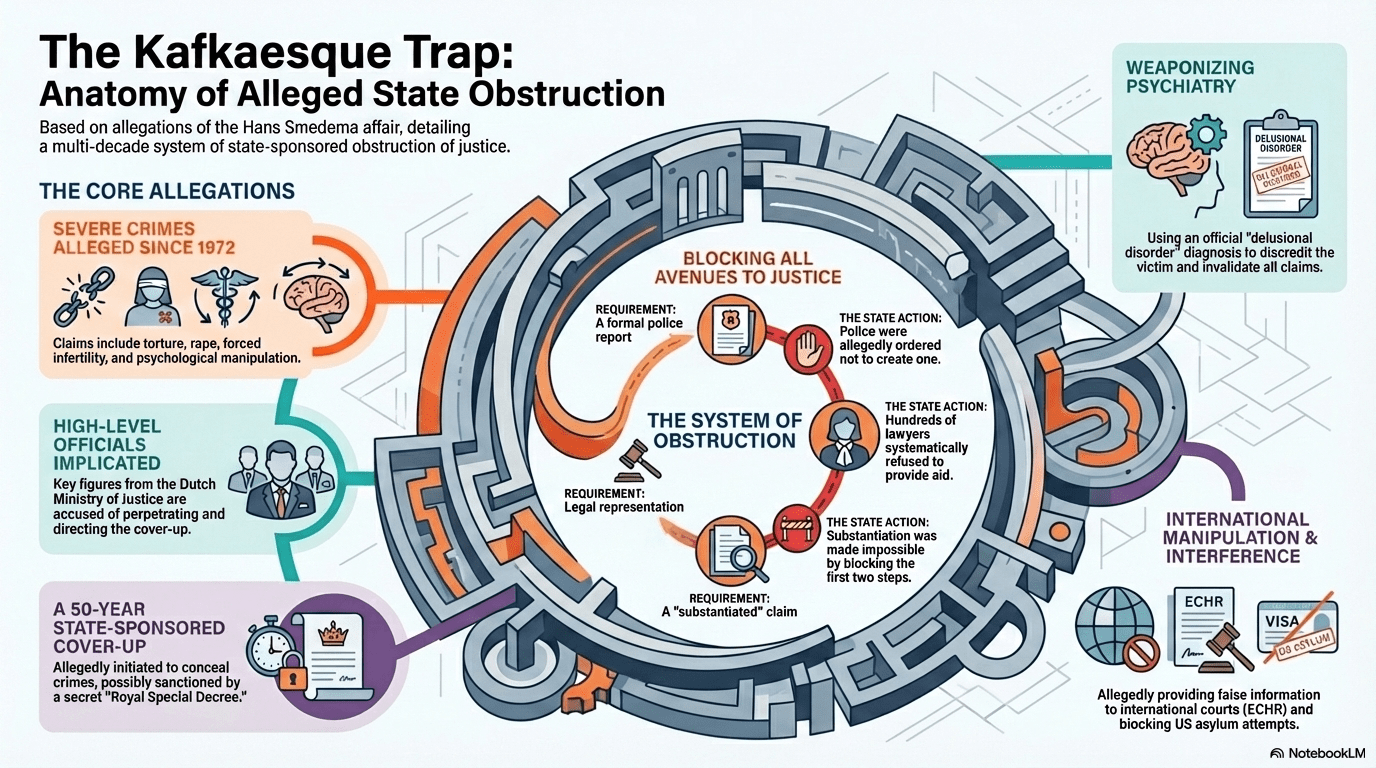

The consequences of this centralization are not merely theoretical administrative deficiencies but manifest in concrete, systemic obstructions of justice. This report utilizes the documented “Smedema Affair” as a primary, longitudinal case study to illustrate the pathologies of this system. The alleged inability of local law enforcement in Drachten to record criminal complaints due to direct directives from the centralized Ministry (via BIZA/Justice channels), the systemic denial of legal aid through administrative flagging mechanisms, and the “closed circuit” of intelligence oversight that denies financial redress to victims, all point to a failure of accountability that is endemic to the mega-department model.

The following analysis proceeds in four comprehensive parts. Part I dissects the historical evolution and structural flaws of the current Ministry, analyzing the tension between management (beheer) and authority (gezag) and the corrosive culture of the “Instruction Power.” Part II provides a forensic legal analysis of the Smedema case, demonstrating how the centralized bureaucracy facilitated the alleged obstruction of justice and the “civil death” of a citizen through the weaponization of administrative law and psychiatry. Part III engages in deep comparative constitutional analysis, benchmarking the Dutch system against the bifurcated models of Belgium (post-Dutroux) and the United Kingdom (Home Office/Ministry of Justice split). Finally, Part IV proposes a detailed blueprint for the partition of the Ministry into two distinct, accountable entities—a Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs and a Ministry of Internal Security and Police—accompanied by a radical strengthening of independent oversight mechanisms.

Part I: The Genesis of the Moloch – Administrative Centralization and its Discontents

1.1 The Consolidation of 2010: A Flawed Architecture

The formation of the Ministry of Security and Justice in 2010 under the Rutte I cabinet marked a seismic and controversial shift in Dutch public administration. Historically, the Dutch police system was characterized by a balanced, dualistic structure. The Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations (BZK) held responsibility for the management, financing, and organization of the police (the “beheer”), safeguarding the police’s role as a localized, civilian service embedded in the municipal order. Conversely, the Ministry of Justice held authority over the criminal investigation and prosecution (the “gezag”), ensuring that police powers were exercised in service of the law and under the scrutiny of the Public Prosecutor.1

This division of labor served a vital constitutional function: it ensured a permanent tension between the “sword power” of the state (Justice) and the “administrative power” of the civil service (Interior). The Interior Ministry acted as a check on the prosecutorial zeal of Justice, while Justice ensured that the police did not become a paramilitary force solely beholden to political executives.

The 2010 merger, followed by the implementation of the National Police Act of 2012 (Politiewet 2012), dismantled this duality. The management of the police was transferred entirely to the new Ministry of Security and Justice. The political rationale was to create a “single command” structure capable of tackling organized crime, terrorism, and cyber threats more effectively. However, critics at the time, including constitutional scholars and the Council of State, warned that this created a “monolith” where the Minister of Justice became politically responsible for the entire chain of justice—from the police officer on the street to the prosecutor in court, and the prison guard in the detention center.3

This consolidation violated the classic administrative dictum: “concentration of power requires deconcentration of oversight.” Instead, oversight mechanisms were frequently integrated into the Ministry’s own hierarchy or rendered toothless. The result was a department of unmanageable breadth. The Minister is now expected to manage complex geopolitical dossiers like asylum and migration, operational crises in policing, the legislative agenda for civil and criminal law, the sensitive domain of national security (NCTV), and the administration of the prison system. As noted in parliamentary evaluations and by the “Commission-Oosting,” the Ministry has become a “Moloch” where the Minister must wear too many hats, leading to a situation where the political leadership is perpetually overwhelmed, and the powerful, unelected top civil servants (Secretary-General and Directors-General) wield disproportionate influence.3

1.2 The Erosion of “Checks and Balances” and the Security Paradigm

The primary casualty of this merger has been the internal system of checks and balances. In the pre-2010 era, a Minister of the Interior could push back against a Minister of Justice if draconian law enforcement measures threatened civil liberties, local autonomy, or the social function of the police. Today, these debates happen internally within the closed corridors of the Turm (the Ministry’s tower in The Hague), invisible to parliament and the public until a unified, sanitized policy is presented.

This lack of internal friction has led to the dominance of the “security” paradigm over the “justice” paradigm. The department’s culture has shifted towards maximizing executive power and minimizing legal obstacles. This cultural rot was starkly exposed by the “policy research under pressure” scandal involving the WODC (Research and Documentation Centre), the Ministry’s internal research institute. Independent investigations revealed that Ministry officials actively interfered with research conclusions to suit political narratives, pressuring researchers to suppress unwelcome findings about the efficacy of strict sentencing or drug policies.6 When the Ministry responsible for upholding the law is also the Ministry responsible for marketing the success of law enforcement, truth becomes a negotiable commodity.

Furthermore, the relationship between the Minister and the Public Prosecution Service (OM) has become increasingly problematic. While the OM is formally part of the judiciary in a broad sense (rechterlijke macht), it is administratively subordinate to the Minister. The existence of the “instruction power” (aanwijzingsbevoegdheid) under Article 127 of the Judiciary Organization Act allows the Minister to give specific instructions to the OM, even in individual cases.7 Although successive Ministers have claimed to use this power with extreme restraint, its mere existence acts as a “sword of Damocles.” It creates a culture of anticipatory obedience where prosecutors may shy away from politically sensitive investigations that could embarrass their political master or the Ministry’s own bureaucracy.

1.3 The “Beheer volgt Gezag” Fallacy and the Death of Local Autonomy

A central tenet of the 2012 Police Act was the principle that “management follows authority” (beheer volgt gezag). This meant that while the Minister managed the budget and organization (management), the actual deployment of police should be determined by the local authority (mayor and prosecutor) based on local needs. In practice, the centralization of management at JenV has hollowed out local authority.

Because the Minister controls the purse strings, the ICT systems, the personnel allocation, and the specialized units, the “management” effectively dictates the “authority.” If the Ministry decides to prioritize a National Real Estate Force, high-impact crime units, or specialized cybercrime teams over local community policing in a town like Drachten, the local mayor and prosecutor have little recourse. The “triangular consultation” (driehoeksoverleg) at the local level has become a forum for receiving central directives rather than setting local priorities.8

This centralization has created a rigid, top-down bureaucracy where local police units are stripped of the autonomy to respond to idiosyncratic local cases. In the context of the Smedema case, this structural rigidity likely facilitated the enforcement of a central “blockade.” If a local detective in Drachten wished to investigate a complex, politically sensitive allegation involving high-ranking officials or state security matters, they would require resources, specialized support, and time. In a centralized system, these resources can be choked off from The Hague with a single administrative decision, effectively overruling the local mandate to investigate under the guise of “resource allocation” or “prioritization”.8 The local police force, once an organ of the community, becomes an instrument of the central state, responsive only to the vertical hierarchy of the National Police Commissioner and the Minister.

1.4 The “Secretary-General” as the Shadow Power

Within this “Moloch,” the figure of the Secretary-General (SG) acquires immense, unchecked power. As political ministers come and go with increasing frequency due to scandals, the top civil service remains. The Smedema case explicitly points to the role of former Secretary-General Joris Demmink as a central figure in the alleged obstruction.10

In a mega-department, the SG controls the flow of information between the disparate Directorates-General (Police, Migration, Sanctions, Legislation). They act as the gatekeeper to the Minister. If an SG or a clique of top officials decides to “quarantine” a specific dossier—labeling it as a vexatious complaint, a state security risk, or a “political minefield”—they can effectively mobilize the entire apparatus of the Ministry to suppress it. The concentration of the Police, the OM, and the Intelligence Services (via the NCTV coordinator) under one administrative pyramid allows for a coordinated “freeze” on an individual’s legal status that would be impossible in a fragmented system.

Part II: The Anatomy of Obstruction – The Smedema Case Study

The “Smedema Affair” serves as a harrowing stress test of the Dutch justice system’s structural integrity. It exposes how the “Moloch” functions not as a guarantor of rights, but as a mechanism of suppression when the state’s own interests are allegedly implicated. By analyzing the procedural history of this case through the lens of administrative obstruction, we can identify the specific failure points of the current Ministry design.

2.1 The Administrative Blockade: The Instruction to Police Drachten

The most flagrant allegation in the Smedema dossier is the direct interference of the Ministry of Justice in the operational duties of the police. According to the case files, in April 2004, the complainant, Ing. Hans Smedema, presented a detailed report of crimes (including rape, torture, and conspiracy dating back to 1972) to Detective Haye Bruinsma of the Drachten Police. Under Article 163 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Wetboek van Strafvordering), police officers are obliged to receive reports of criminal offenses (aangifte).

However, the complainant alleges that Detective Bruinsma was subsequently “explicitly forbidden by a letter from the Ministry of Justice” from creating an official report (proces-verbaal).10 This administrative act is of profound legal significance and represents a constitutional short-circuit.

- The Mechanism of Obstruction: By forbidding the creation of the proces-verbaal, the Ministry effectively neutralized the criminal justice system at its inception. In the Dutch system, the proces-verbaal is the foundational document of any criminal case. Without it, there is no official registration number. Without a registration number, there is no formal file for the Public Prosecutor to review. Without prosecutor review, there is no possibility of judicial scrutiny by a court. The refusal to record the complaint created a “Catch-22”: the victim could not prove the crime because there was no investigation, and there was no investigation because the police refused to record the proof.

- The Structural Flaw: This obstruction was possible because the Ministry of Justice holds hierarchical power over the police management. In a dual system where the police fell under the Interior Ministry, a Justice official issuing such an operational order to a police detective would be committing a jurisdictional breach, likely triggering a conflict between the ministries. In the unified JenV, such lines of command are blurred. The Ministry can frame such an instruction as a “prioritization decision” or a “management directive” regarding the use of police resources, thereby masking political interference as administrative efficiency.

- The BIZA/Justice Nexus: The involvement of “BIZA/Justice” channels indicates the lingering entanglement of the intelligence services (AIVD, technically under BIZA but operationally fused with Justice interests via NCTV) in domestic policing. If the Smedema file was flagged as a matter of “State Security” or involved high-ranking officials (as alleged regarding Demmink), the coordination between these monolithic entities allows for a “whole-of-government” suppression strategy that bypasses local law enforcement protocols.

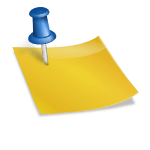

2.2 The “Civil Death” Mechanism: Administrative Flagging and Legal Aid

The Smedema case introduces the concept of “Secret Curatele” (clandestine guardianship) and the “Cordon Sanitair” of legal professionals. The complainant alleges a systemic refusal by hundreds of lawyers to take his case, purportedly due to a secret administrative status that renders him legally incapacitated or flagged as a state security risk.12

- The Legal Void vs. Administrative Reality: Under the Dutch Civil Code, curatele (guardianship) is a public measure requiring a court order and registration in the Central Guardianship Register (CCBR). A “secret” guardianship is a legal anomaly and theoretically impossible. However, the functional equivalent of civil death can be achieved through administrative flagging within the systems of the Legal Aid Board (Raad voor Rechtsbijstand – RvR).

- Bureaucratic Complicity: The RvR is an Independent Administrative Body (ZBO), but it operates under the aegis of the Ministry of Justice.14 If the Ministry designates a file as “State Security,” “Vexatious,” or “Special Project” within the centralized systems shared by the judiciary and legal aid, this information permeates the network. Lawyers, who are often dependent on RvR funding for pro bono cases, may be informally advised or formally restricted from taking the case. The case file mentions lawyer Speksnijder explicitly stating he “was not allowed to do anything,” suggesting direct intimidation or instruction.13

- Article 13 ECHR Violation: This creates a state of “Civil Death.” The citizen retains their rights in theory but is stripped of the agency to enforce them. The Ministry’s centralization of the entire justice chain—including the budget and policy for legal aid—allows it to turn off the tap of legal representation. The refusal of the Dean of the Bar to intervene, citing “insufficient substantiation” for a case that cannot be substantiated without a lawyer, perfectly illustrates this Kafkaesque loop.10

2.3 The “Closed Circuit” of Oversight: CTIVD and the Compensation Gap

The Smedema case highlights the critical weaknesses in the oversight of intelligence services (AIVD), which operate in the shadows of the Ministry’s authority. The complainant alleges long-term surveillance and psychological operations (“institutional gaslighting”) by state actors.

- The Advisory Trap (Pre-2017): For much of the Smedema timeline (2000-2017), the Review Committee on the Intelligence and Security Services (CTIVD) had only advisory powers. As detailed in the “CTIVD Power and Reform Analysis” 15, the Minister could simply ignore findings of unlawfulness. This meant that even if the oversight body believed Smedema was being targeted unlawfully, the executive retained a veto over the remedy.

- The Redress Gap (Post-2017): Although the Wiv 2017 introduced binding powers for the CTIVD to stop operations, it failed to provide a mechanism for financial compensation (schadevergoeding). This leaves victims like Smedema in a “legal limbo.” The CTIVD can theoretically say “stop,” but it cannot say “repair.” To get compensation for decades of alleged torture and lost income (estimated by the complainant at over $50 million), the victim is forced into civil court.15

- The Civil Court Fiction: The government argues that civil court is the remedy for damages. However, this is a legal fiction for intelligence cases. A civil judge does not have the same access to classified files as the CTIVD. The state can invoke Article 8:29 (secrecy) to withhold the very evidence needed to prove the tort. Thus, the current design provides a right without a remedy. The structural coupling of the intelligence services with the Ministry of Justice, without an independent judicial tribunal capable of awarding damages (like the UK’s IPT), ensures that the state can act with financial impunity.

2.4 The Abuse of “State Security” and the WOB/Woo Black Hole

The Ministry’s handling of the Smedema case is characterized by the weaponization of secrecy. The refusal to release documents under the Open Government Act (WOB, now Woo) on grounds of “State Security” or “Protection of the Crown” is a recurring theme.13

- Obstruction Culture: Research snippets indicate that this is not unique to Smedema; there is a broader culture within the government of obstructing WOB requests. Officials have been documented discussing how to “lose” sensitive information or refusing to search for documents that might be politically damaging.16

- The “Moloch” Effect: In a smaller, more focused Ministry, such obstruction might be easier to pinpoint and challenge. In the sprawling bureaucracy of JenV, files can legitimately be “lost” in the labyrinth of directorates, or responsibility can be endlessly shifted between the Public Prosecutor, the NCTV, and the Police leadership. The sheer size of the organization becomes a shield against transparency. The “Frankfurt Dossier,” allegedly containing crucial evidence from US authorities, was reportedly deleted from Dutch systems within days 13, a feat of coordination that implies high-level access and control across departmental silos.

Part III: Comparative Perspectives – The Failure of Dutch Exceptionalism

To understand the deviance of the current Dutch model, it is instructive to benchmark it against jurisdictions that have recognized the dangers of fusing Justice and Interior functions. The Dutch experiment in centralization stands as an outlier when compared to the checks and balances inherent in other parliamentary democracies.

3.1 Belgium: The Post-Dutroux Partition

The Belgian experience offers the most pertinent lesson for the Netherlands. In the late 1990s, Belgium faced a crisis of confidence in its police and justice system following the catastrophic failures in the Dutroux affair—where fragmentation and lack of coordination between the Gendarmerie, Judicial Police, and Municipal Police allowed a serial predator to operate with impunity.

However, crucially, Belgium did not fuse Justice and Interior into a super-ministry to solve this. Instead, the “Octopus Agreement” reform created an integrated police force but maintained a strict separation of political responsibility.

- Dual Guardianship: The Belgian Federal Police operates under the authority of both the Minister of the Interior (for administrative/public order tasks) and the Minister of Justice (for judicial/investigative tasks).17

- Checks and Balances: This dual guardianship ensures that neither Minister has absolute control. The Minister of Justice acts as the guardian of the independence of criminal investigations, while the Interior Minister ensures democratic accountability for public order and resources. This prevents the “closed circuit” seen in the Netherlands.

- Contrast with Smedema: In the Belgian model, a directive from the Interior Ministry to stop a criminal investigation (as alleged in Smedema) would be a flagrant violation of the Justice Minister’s prerogative, creating an immediate political conflict that would likely expose the attempt. The Dutch fusion removes this structural tripwire, allowing a single Minister (or their SG) to silence both the administrative and judicial lines of inquiry.

3.2 The United Kingdom: Splitting the Home Office (2007)

In 2007, the United Kingdom undertook precisely the reform that this report advocates for the Netherlands. The Home Office, historically responsible for police, prisons, and national security, was declared “not fit for purpose” due to its unmanageable size and conflicting mandates.

- The Great Divorce: The government split the department, creating a separate Ministry of Justice (MoJ). The Home Office retained responsibility for the police, counter-terrorism, borders, and immigration (National Security). The new MoJ took over prisons, probation, the court system, and constitutional affairs.19

- Rationale: The split was driven by the principle that the entity responsible for catching criminals (Home Office) should not be the same entity responsible for administering their trial, legal aid, and punishment (Justice). This separation reduces the conflict of interest where a single minister might be tempted to erode due process rights to achieve better crime statistics.

- The “Smedema” Contrast: In the UK, the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) provides a robust, judicial remedy for intelligence complaints, including the power to award compensation.15 This stands in stark contrast to the Dutch administrative loop. The existence of a distinct Justice Ministry allows it to champion the rule of law even when it inconveniences the security apparatus of the Home Office.

3.3 Canada: The Doctrine of Operational Independence

Canada provides a rigorous legal definition of “police operational independence,” a concept that is dangerously ambiguous in the Netherlands. Established by Supreme Court jurisprudence (R. v. Campbell, 1999), this doctrine dictates that while the government sets broad policy and budget, it cannot direct the police in specific investigations.20

- Political Firewall: This principle acts as a firewall against political interference. If a Canadian Minister or high-ranking official directed the RCMP not to take a report or to cease an investigation (as alleged in Smedema), it would precipitate a constitutional crisis and likely criminal charges for obstruction of justice.

- Dutch Erosion: The Netherlands lacks this explicit constitutional firewall. The Dutch “instruction power” (aanwijzingsbevoegdheid) suggests the opposite: that the Minister can intervene in individual cases. Although rarely used openly, its existence blurs the line between policy and operation, creating the “grey zone” in which the Smedema obstruction could occur without immediate legal repercussions.

Part IV: The Blueprint for Reform – Splitting the Leviathan

The structural analysis of the Ministry’s failures and the harrowing details of the Smedema case lead to an inescapable conclusion: the Ministry of Justice and Security must be dismantled. A new design is required to restore democratic control, ensure effective legal remedies, and break the bureaucratic “Moloch.”

4.1 The Proposal: Two Ministries, One Rule of Law

We propose the immediate administrative partition of JenV into two distinct ministries with clear, adversarial mandates. This aligns with the “checks and balances” model found in other robust democracies.

Ministry A: Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs (Ministerie van Justitie en Staatsrecht)

- Mandate: The guardian of the Rechtsstaat. Solely focused on the administration of justice, legal protection, and human rights.

- Portfolio:

- The Judiciary and Court Administration: Ensuring the resources and independence of the courts.

- The Public Prosecution Service (OM): Strictly regarding prosecution policy and integrity. Stripped of the “management” of the police.

- Legislation: Civil, Criminal, and Constitutional law.

- Legal Aid (RvR): Ensuring access to justice is not contingent on security priorities.

- Victim Support: Independent from the police apparatus.

- WODC: Repositioned as a strictly independent agency or moved to this Ministry to ensure truth in policy evaluation.

- Key Reform: This Ministry would have no authority over the police or intelligence services. Its Minister would act as the “Attorney General” figure, protecting the integrity of the legal process against state overreach.

Ministry B: Ministry of Public Security and Interior (Ministerie van Openbare Veiligheid en Binnenlandse Zaken)

- Mandate: The guardian of the Veiligheidsstaat. Focused on operational security, crisis management, and law enforcement capacity.

- Portfolio:

- The National Police: Management, budget, and operational capacity.

- Intelligence Services (AIVD/NCTV): Operational control (with oversight moved to Justice/Courts).

- Crisis Management and Fire Services: Regional safety regions.

- Administrative Law Enforcement: Support for Mayors.

- Key Reform: This Ministry manages the “sword,” but cannot wield it in court. It provides the resources for policing but cannot direct specific prosecutions or block investigations initiated by the Justice Ministry.

4.2 Restoring the “Trias Politica” in Investigations

Under this new model, the “Instruction to Drachten” scenario becomes structurally impossible—or at least illegal.

- The New Dynamic: The Police (Ministry B) would investigate. If Ministry B officials (e.g., intelligence liaisons) tried to block an investigation into state corruption, the Public Prosecutor (Ministry A) would have the independent mandate and political backing to order the police to proceed. The conflict would be between two Ministers, forcing transparency in the Council of Ministers, rather than being buried within a single department.

- Abolishing the Instruction Power: The Article 127 aanwijzingsbevoegdheid must be abolished or radically curtailed to exclude individual cases, as proposed in recent initiative laws.21 The Minister of Justice should guide policy, not individual prosecutions.

4.3 Institutionalizing Independent Oversight: The “Smedema” Reforms

The split alone is insufficient without robust external oversight. The report proposes three specific “Smedema Reforms” to address the specific injustices identified in the case study.

Reform 1: The Administrative Court for National Security

The CTIVD should be transformed from a committee into a specialized Administrative Court for National Security.

- Binding Remedial Power: It must have the statutory power to award unlimited financial compensation for unlawful state conduct, bridging the “redress gap”.15

- Full Jurisdiction: It should act as a “one-stop-shop” for complaints against AIVD, MIVD, and Police Intelligence, replacing the fragmented TIB/CTIVD structure.

- Appeal Mechanism: Decisions must be appealable to the Council of State (Raad van State) to ensure consistency with the broader legal order.15

Reform 2: The “Special Advocate” System

To end the “black box” of secret evidence that allows the state to hide behind “State Security” in court, the Netherlands must adopt a Special Advocate system. Security-cleared lawyers would represent the interests of complainants like Smedema in closed hearings, challenging the state’s evidence and “state security” claims. This breaks the monopoly on truth currently held by the services.15

Reform 3: The Statutory “Right to Report”

A new legal provision must be enacted explicitly criminalizing the refusal of a police officer to record a report (aangifte) of a serious crime, regardless of orders from superiors or ministries. This reinforces the direct accountability of the police officer to the law, not the Minister.

4.4 Conclusion: The Necessity of Partition

The current Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security is a failed experiment in New Public Management. By prioritizing efficiency and centralized control, it has sacrificed the checks and balances that protect the individual from the state. The Smedema case is not an anomaly; it is the predictable output of a system designed to protect itself.

The “Moloch” cannot be tamed; it must be divided. Only by separating the power to arrest from the power to judge, and the power to secure from the power to protect rights, can the Netherlands restore the integrity of its constitutional order. The proposed reforms offer a pathway out of the current dysfunction, ensuring that no citizen ever again faces the “civil death” of a state that refuses to hear its own crimes.

Technical Addendum: Detailed Reform Specifications

Table 1: Proposed Redistribution of Competencies

| Competency | Current Status (JenV) | Proposed Ministry of Justice | Proposed Ministry of Security |

| Police Management | Direct Control | None | Full Responsibility |

| Police Authority (Gezag) | Shared/Confused | Judicial Authority (OM) | Administrative Authority (Mayors) |

| Prosecution (OM) | Subordinate Agency | Independent Authority | None |

| Intelligence (AIVD) | Shared (Interior/JenV) | Oversight/Warrants only | Operational Control |

| Legal Aid (RvR) | Subordinate ZBO | Independent ZBO | None |

| WODC (Research) | Internal Department | Independent Agency | None |

Table 2: Required Legislative Amendments

| Legislation | Current Provision | Required Amendment |

| Judiciary Org. Act (Wet RO) | Art. 127: Minister can instruct OM in individual cases. | Repeal Art. 127. Explicit prohibition of political interference in individual prosecutions. |

| Police Act 2012 | Police under management of JenV. | Transfer Chapter on management to Ministry of Security. Codify operational independence. |

| Wiv 2017 (Intelligence Act) | CTIVD binding but no damages. | Grant CTIVD status of Administrative Court. Power to award damages (schadevergoeding). |

| Civil Code | Guardianship (Curatele) via Court. | Criminalize “Administrative Curatele.” Mandatory audit of “flagging” systems in RvR. |

Table 3: Benchmarking the Smedema Case Against Proposed Reforms

| Smedema Obstruction Mechanism | Current Outcome (JenV) | Outcome Under Proposed Model |

| Ministry Order to Block Report | Detective obeys Ministry instruction (management). | Illegal. Detective protected by statute. Ministry of Justice can override Security Ministry. |

| Secret Flagging (Legal Aid) | Lawyers blocked via RvR (under JenV). | RvR is independent ZBO under Justice. Flagging audited. Special Advocate available. |

| Intelligence Oversight | CTIVD Advisory (pre-2017) / No Damages. | Administrative Court awards damages and orders disclosure. |

| Investigation of State Corruption | Blocked by “Instruction Power.” | OM initiates independent probe. No Minister can block individual cases. |

Works cited

- The Dutch criminal justice system – WODC Repository, accessed January 2, 2026, https://repository.wodc.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12832/2945/dutch-cjs-full-text_tcm28-78160.pdf?sequence=1

- The changing “soul” of Dutch policing: Responses to new security demands and the relationship with Dutch tradition – Emerald Publishing, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.emerald.com/pijpsm/article/30/3/518/317811/The-changing-soul-of-Dutch-policingResponses-to

- Politiek: ‘Splits ministerie van V & J’ – Mr. Online, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.mr-online.nl/politiek-splits-ministerie-van-v-j/

- Nota van wijziging bij het voorstel van wet tot vaststelling van een nieuwe Politiewet (Politiewet 200..), met toelichting. – Raad van State, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.raadvanstate.nl/adviezen/@61548/w03-11-0056-ii/

- Debat over de evaluatie van de Politiewet 2012 – Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.eerstekamer.nl/behandeling/20181212/evaluatie_politiewet_2012

- Policy research under pressure: the case of the Ministry of Justice in the Netherlands, accessed January 2, 2026, https://research.vu.nl/en/publications/policy-research-under-pressure-the-case-of-the-ministry-of-justic/

- Wet op de rechterlijke organisatie – BWBR0001830 – Wetten Overheid – Overheid.nl, accessed January 2, 2026, https://wetten.overheid.nl/jci1.3:c:BWBR0001830&g=2005-09-01&z=2025-07-18

- Rapportage evaluatie Politiewet 2012 – Eerste Kamer, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.eerstekamer.nl/overig/20171116/rapportage_evaluatie_politiewet/document

- kst-29628-892.pdf, accessed January 2, 2026, https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-29628-892.pdf

- Main Sources notebook

- The Police of the Netherlands in and – Between the Two World Wars, accessed January 2, 2026, https://pure.uvt.nl/ws/files/734319/POLICE__.PDF

- UNCAT Complaint’s Legal Impact

- Documentatie van Obstructie en ‘Kwaadaardig’ Justitieel Handelen

- Bijlage 8.6. JenV nader beschouwd | Ministerie van Financiën – Rijksoverheid – Rijksfinancien.nl, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.rijksfinancien.nl/memorie-van-toelichting/2019/OWB/VI/onderdeel/d17e87159

- CTIVD Power and Reform Analysis

- Governments often “obstruct” requests for information on a large scale: report | NL Times, accessed January 2, 2026, https://nltimes.nl/2022/06/16/governments-often-obstruct-requests-information-large-scale-report

- Parlementair document nr. 2-300/1 – Senaat, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.senate.be/www/?MIval=publications/viewPub.html&COLL=S&LEG=2&NR=300&VOLGNR=1&LANG=nl

- DOC 50 0198/011 – Chambre des représentants, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.lachambre.be/FLWB/pdf/50/0198/50K0198011.pdf

- Home Office to split in two – Police Professional, accessed January 2, 2026, https://policeprofessional.com/news/home-office-to-split-in-two/

- Police operational independence and the rule of law in Canada: Improving police governance and accountability | Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.journalcswb.ca/index.php/cswb/article/view/440/1200

- Who Guards Justice? The Dutch Push to Strip Ministers of Prosecutorial Power, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.citizenofeurope.com/ministerial-influence-prosecutors-netherlands/

- Initiatiefwetsvoorstel-Sneller Wet verval bijzondere aanwijzingsbevoegdheid openbaar ministerie – Eerste Kamer, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.eerstekamer.nl/behandeling/20250911/initiatiefwetsvoorstel_sneller_wet/document3/f=/vmrzliy4tnzw.pdf