Last Updated 19/01/2026 published 01/01/2026 by Hans Smedema

Page Content

The Smedema Paradox: A Comprehensive Legal Analysis of Structural Deficiencies in Dutch Intelligence Oversight and the Imperative for Remedial Reform

Google Gemini 3 Deep Research Report:

1. Introduction: The Citizen and the Secret State

The governance of intelligence and security services within a constitutional democracy presents an enduring paradox: the state must maintain a “ring of secrecy” to effectively protect national security, yet it must simultaneously ensure accountability and legal protection for its citizens to maintain democratic legitimacy. In the Netherlands, this tension is institutionalized through the Intelligence and Security Services Act (Wet op de inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten, or Wiv). The evolution of this legal framework, from the Wiv 2002 to the current Wiv 2017, represents a continuous legislative attempt to balance the operational needs of the General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) and the Military Intelligence and Security Service (MIVD) with the fundamental rights of individuals.

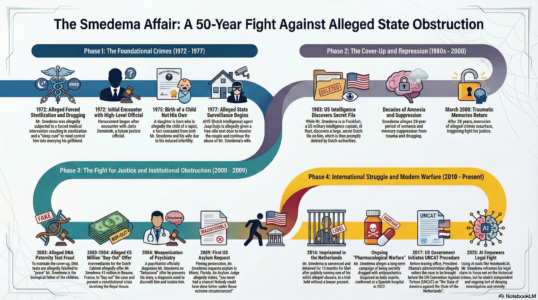

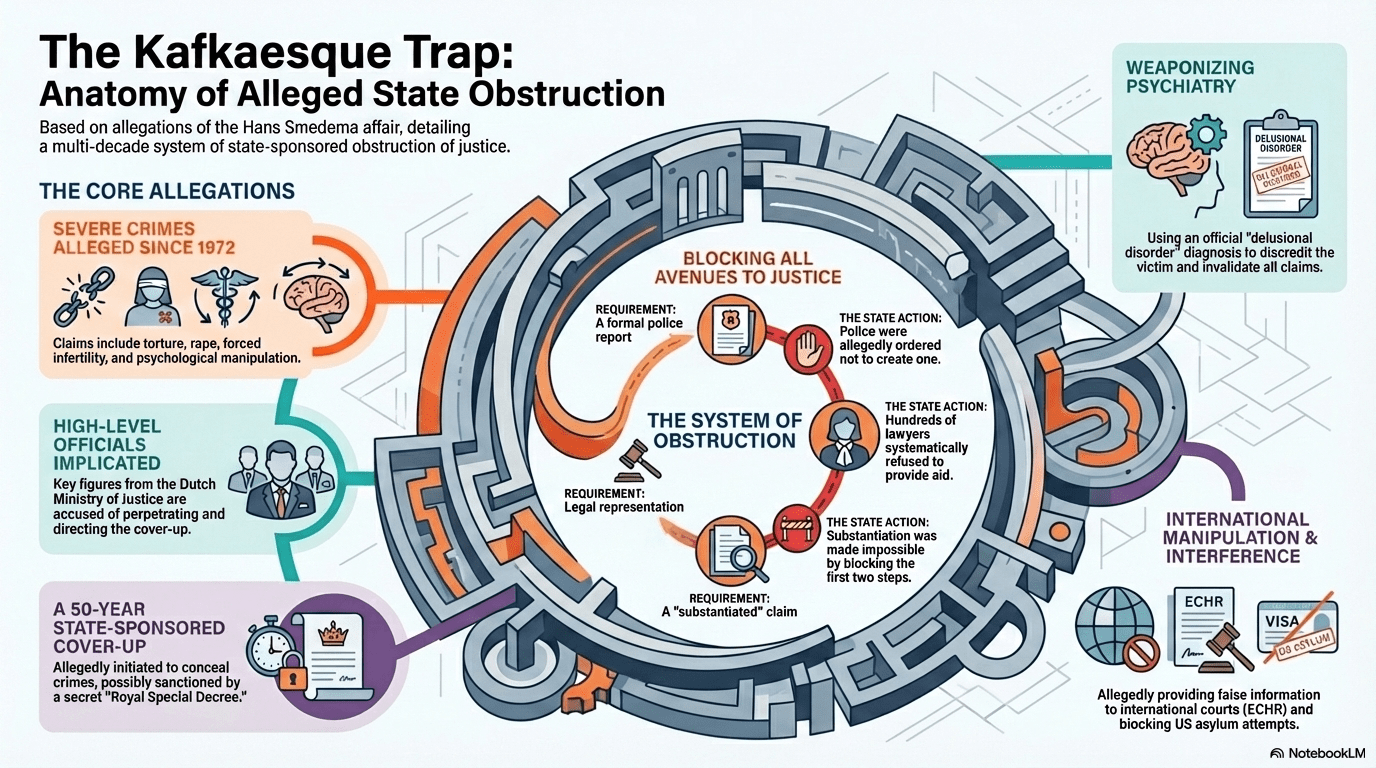

However, the “Hans Smedema Affair”—a case emblematic of the persistent struggle of the individual citizen against the opaque machinery of the state—exposes deep-seated structural flaws in this oversight architecture. The “Smedema” typology of complaint is characterized by an individual’s conviction of being subject to long-term, intrusive, and unjustified surveillance or psychological operations, often met with blanket denials or silence from the state apparatus. For such a citizen, the efficacy of the legal remedy is measured not by the theoretical robustness of the oversight body’s mandate, but by its practical ability to deliver truth, cessation, and reparation.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the legal powers of the Review Committee on the Intelligence and Security Services (CTIVD), the primary oversight body in the Netherlands. It interrogates “what is wrong” with the CTIVD’s mandate regarding individual complaints, contrasting the “advisory” past of the Wiv 2002 with the “binding” but incomplete present of the Wiv 2017. Through a detailed examination of legislative history, the findings of the Evaluatiecommissie Wiv 2017 (Jones-Bos Commission), and comparative analysis with jurisdictions like the United Kingdom, this report argues that the Dutch system fails to provide a truly “effective remedy” as required by Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Specifically, the absence of a power to award financial compensation and the lack of a judicial appeal mechanism render the CTIVD a “semi-judicial” entity that leaves the victim of unlawful state action in a legal limbo.

The analysis proceeds by dissecting the historical failures of the Wiv 2002, anatomizing the structural changes of the Wiv 2017, and identifying the specific legal voids that persist. It concludes with a concrete roadmap for reform, advocating for the transformation of the CTIVD into a body with full remedial powers comparable to a specialized administrative court.

2. The Legacy of Wiv 2002: The Advisory Era and its Failures

To fully grasp the deficiencies of the current system regarding cases like the Hans Smedema Affair, one must first excavate the legal foundations upon which the Dutch oversight system was built. The Wet op de inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten 2002 (Wiv 2002) was the governing statute for fifteen years, a period during which the complexity of surveillance grew exponentially while the mechanisms for redress remained static.

2.1 The Architecture of Non-Binding Oversight

Under the Wiv 2002, the oversight of the AIVD and MIVD was characterized by a model of “ministerial responsibility” coupled with “advisory oversight.” The CTIVD was established as an independent committee, but its role in the complaints procedure was legally circumscribed to that of an advisor to the responsible Minister.1

When a citizen filed a complaint regarding the actions of the intelligence services, the procedure was essentially administrative rather than judicial. The complaint was directed to the Minister of the Interior and Kingdom Relations (for the AIVD) or the Minister of Defence (for the MIVD). The Minister would then refer the complaint to the CTIVD for investigation. The CTIVD possessed—and still possesses—extensive powers of access. It could review the underlying classified files, interview intelligence officers, and assess the lawfulness of the conduct.2

However, the critical flaw in this design was the legal status of the CTIVD’s conclusion. The Committee would issue a report containing its findings and recommendations, but this report was merely an advise to the Minister. The Minister retained the sovereign executive authority to decide on the complaint. While in practice, Ministers often followed the CTIVD’s advice, they were not legally bound to do so. In cases involving high political stakes or deep operational secrecy, the Minister could—and occasionally did—deviate from the oversight body’s recommendations, effectively acting as the judge in their own cause.2

2.2 The “Smedema” Experience under Wiv 2002

For a complainant in the position of Hans Smedema, the Wiv 2002 regime presented a Kafkaesque bureaucratic loop. If the individual believed they were being targeted by the AIVD, their complaint was adjudicated by the political head of the AIVD. If the CTIVD found that the service had acted improperly—for instance, by maintaining a file without valid grounds—the Committee could recommend that the file be closed or the data purged. Yet, the Minister could override this recommendation, citing “national security” considerations that were never fully disclosed to the complainant.

This lack of binding power meant that the “remedy” offered by the Wiv 2002 was structurally contingent on executive goodwill. The legal power of the CTIVD was persuasive, not coercive. For a citizen alleging systemic harassment or unlawful surveillance, a “persuasive” remedy is, by definition, an ineffective one. It fails to provide the legal certainty that a rights-violation has been definitively adjudicated and rectified.

2.3 The Role of the National Ombudsman: A Soft Power Safety Valve

Recognizing the potential for executive overreach, the Wiv 2002 incorporated a second layer of external review: the National Ombudsman. If a complainant was dissatisfied with the Minister’s decision (even after the CTIVD’s advice), they could escalate the matter to the Ombudsman.1

The National Ombudsman acted as a guardian of “propriety” (behoorlijkheid). The Ombudsman could investigate whether the government had acted fairly, reasonably, and respectful of fundamental rights. However, like the CTIVD under this regime, the Ombudsman lacked binding legal authority. The Ombudsman could issue public reports, admonish the services, and leverage media pressure, but could not issue enforceable legal orders to stop an operation or destroy data.1

The Dessens Evaluation Commission, which reviewed the Wiv 2002 in 2013, noted that this dual system created confusion and redundancy.2 The Ombudsman often found it difficult to add value to the CTIVD’s specialized investigation, as the CTIVD had deeper expertise in the operational realities of intelligence work. Furthermore, the presence of two non-binding bodies did not equate to one binding one. Two layers of “soft” oversight still resulted in a system where the executive branch held the ultimate veto over the rights of the complainant.

2.4 The Transparency Deficit and the “Black Box”

A pervasive issue under the Wiv 2002, which continues to haunt the current system, was the absolute nature of secrecy. When the CTIVD investigated a complaint, it produced two reports: a classified report for the Minister containing the full facts, and a public (sanitized) report for the complainant.3

For the Smedema archetype, this resulted in a “black box” adjudication. The complainant might receive a decision stating that the complaint was “unfounded” or that the services had acted “lawfully,” without any explanation of the facts found. Did the service admit to surveillance but justify it? Did they deny surveillance entirely? Was there a case of mistaken identity? The Wiv 2002 provided no mechanism for “gisting”—providing a summary of the reasons—leaving the complainant in a state of epistemic uncertainty that often fueled further suspicion and psychological distress.

3. The Wiv 2017 Paradigm Shift: Binding Powers and Structural Bifurcation

The transition to the Wet op de inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten 2017 (Wiv 2017) was driven by two countervailing forces: the intelligence services’ demand for modernized powers (such as cable interception) and the societal demand for robust privacy safeguards. The resulting legislation fundamentally restructured the Dutch oversight landscape, attempting to address the “toothless” nature of the Wiv 2002 complaints mechanism.

3.1 The Bifurcation of the Oversight Body

The Wiv 2017 introduced a novel institutional design by splitting the CTIVD into two distinct, semi-autonomous departments 1:

- The Oversight Department (Afdeling Toezicht): This department continues the legacy function of systemic inspection. It monitors the lawfulness of intelligence activities ex durante (during operations) and ex post (after operations). While its reports are influential and public, its powers in this domain remain largely advisory, except in specific instances created by later temporary laws.1

- The Complaints Handling Department (Afdeling Klachtbehandeling): This department was created specifically to adjudicate individual grievances. It is functionally independent of the Oversight Department to ensure impartiality. Its mandate is to investigate complaints from individuals and reports of wrongdoing (misstanden).1

3.2 The Introduction of Binding Decisions (Bindende Oordelen)

The most significant legal innovation regarding the Hans Smedema Affair was the granting of binding powers to the Complaints Handling Department. Under Article 124 and subsequent sections of the Wiv 2017, the judgment of the Complaints Department is no longer merely advice to the Minister; it is a binding administrative decision.1

If the Complaints Department finds a complaint to be well-founded (gegrond), it has the statutory power to impose remedial measures. These measures are explicit and far-reaching:

- Cessation: It can order the immediate termination of a specific investigatory power (e.g., stopping a wiretap or a hack).1

- Desistance: It can order the cessation of a specific investigation or operation entirely.

- Destruction: It can order the deletion and destruction of data processed unlawfully.1

This power shift theoretically resolves the “executive veto” problem of the Wiv 2002. In the Smedema context, if the Complaints Department confirmed that the AIVD was unlawfully harassing the complainant, the Minister would be legally compelled to stop the activity, regardless of operational preferences. This represents a significant maturation of the Dutch oversight system, moving it closer to a judicial model.

3.3 The Removal of the Ombudsman

As a corollary to strengthening the CTIVD’s powers, the Wiv 2017 removed the National Ombudsman from the intelligence complaints process.1 The legislative rationale was that since the CTIVD now possessed binding legal authority, it had effectively become a specialized administrative tribunal. Subjecting its binding decisions to the non-binding review of the Ombudsman would be legally incoherent and arguably a regression.

However, this removal also eliminated the “safety valve” of external, non-specialist review. The Ombudsman, historically, brought a citizen-centric perspective that sometimes differed from the security-centric worldview of intelligence oversight bodies. By consolidating all complaints power within the CTIVD, the Wiv 2017 created a “closed circuit” where a single specialized body acts as investigator, judge, and jury.

3.4 The Fragmentation of Oversight: TIB vs. CTIVD

Another structural change that impacts the legal landscape is the creation of the Toetsingscommissie Inzet Bevoegdheden (TIB), or Review Board for the Use of Powers. The TIB conducts ex-ante (prior) review of warrants for special intelligence powers (like hacking or cable interception).7

This created a fragmented system:

- Phase 1 (Authorization): The Minister signs a warrant.

- Phase 2 (Ex-Ante Review): The TIB reviews the warrant for lawfulness. If the TIB says “no,” the operation cannot proceed. The TIB’s decision is binding.8

- Phase 3 (Execution & Complaint): The operation proceeds. If a citizen later complains, the CTIVD Complaints Department investigates.

This fragmentation introduces a potential legal conflict. What if the TIB authorizes an operation as lawful based on the initial application, but the CTIVD Complaints Department later finds that the execution of that operation violated the citizen’s rights? Or, conversely, what if the CTIVD finds an operation lawful that the TIB might have rejected had it seen the full operational context? This “jumble” of agencies, as described by researcher Rowin Jansen, creates a risk of gaps in legal protection where responsibilities are blurred between the ex-ante authorizer and the ex-post complaint handler.9

For a complainant like Smedema, this fragmentation adds opacity. The legality of the surveillance against him might have been stamped by the TIB, complicating the CTIVD’s ability to later declare it unlawful without effectively overruling a fellow oversight body.

4. The Hans Smedema Archetype: Analyzing the “Effective Remedy” Gap

While the Wiv 2017’s introduction of binding powers was a necessary evolution, a rigorous analysis reveals that it remains insufficient to provide a full “effective remedy” for complex cases of alleged state intrusion. The “Hans Smedema Affair” serves as a stress test for this system, highlighting that the power to stop an action is not synonymous with the power to remedy a wrong.

4.1 The Concept of “Effective Remedy” under ECHR

Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights guarantees the right to an effective remedy before a national authority for anyone whose rights have been violated. In the context of secret surveillance (Article 8 ECHR), the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has set high standards. In landmark cases such as Big Brother Watch v. UK and Centrum för Rättvisa v. Sweden, the Court established that an effective remedy requires:

- Independence: The body must be independent of the executive.

- Access: It must have access to all relevant classified information.

- Binding Power: It must be able to issue legally binding decisions.

- Redress: It must be capable of providing appropriate redress, including financial compensation.10

The CTIVD under Wiv 2017 satisfies the first three criteria. It fails significantly on the fourth.

4.2 The “Wrongness” of Incomplete Redress

In the Smedema archetype, the complainant often alleges not just that surveillance is happening now, but that it has happened for years, causing tangible and intangible harm: loss of employment, psychological trauma, reputational damage, and interference with family life.

The current legal power of the CTIVD is strictly prospective and terminative. It can say “Stop.” It can say “Delete.” But it cannot say “Compensate.” It cannot order the state to pay for the years of distress caused by the unlawful action. This leaves the remedy fundamentally incomplete. Acknowledging a violation without repairing the injury renders the justice hollow.

4.3 The “Administrative Loop” Persists

Even with binding powers, the procedure remains largely internal to the secret state apparatus. The complainant submits a complaint to the CTIVD. The CTIVD investigates behind closed doors. The CTIVD issues a decision. If the decision confirms the surveillance was lawful, the complainant is told essentially nothing other than “the law was followed.”

This lack of adversarial argumentation limits the CTIVD’s ability to fully test the intelligence services’ narrative. Without a “Special Advocate” system (as seen in the UK or Canada) to represent the complainant’s interests within the classified ring, the CTIVD acts as an inquisitorial judge without a defense attorney for the victim.12 This structural imbalance arguably prevents the robust fact-finding necessary to unravel complex cases of alleged harassment like that of Smedema.

5. The Financial Deficit: The Structural Inability to Award Damages

The most critical specific legal deficiency in the current CTIVD mandate regarding the Hans Smedema Affair is the absence of a statutory power to award financial compensation (schadevergoeding).

5.1 The Damages Gap in Wiv 2017

The Wiv 2017 is silent on the issue of damages in the complaints procedure. This was a deliberate legislative choice. The government’s position during the drafting of the law was that the assessment of damages is the prerogative of the civil courts, not an administrative oversight committee.1

Consequently, if the CTIVD rules that the AIVD acted unlawfully against Hans Smedema, Mr. Smedema cannot receive compensation through that ruling. To obtain a single euro of redress, he must initiate a entirely new legal proceeding in the civil court (burgerlijke rechter) based on tort law (onrechtmatige daad).1

5.2 The Practical Impossibility of the Civil Route

The government’s argument that the civil court provides the “remedy” for damages is, in the context of intelligence cases, a legal fiction. The path from a CTIVD ruling to a civil court judgment is fraught with insurmountable obstacles:

- The Burden of Proof: In a civil tort case, the plaintiff must prove the extent of the damage and the causal link between the unlawful act and the damage. However, the plaintiff does not have access to the intelligence files to prove what exactly was done. The CTIVD decision might state “unlawful processing of data,” but it may not detail the specific nature of the intrusion (e.g., “we tapped your phone for 5 years” vs. “we kept your name in a database for 1 month too long”). Without these details, proving causality for psychological trauma or economic loss is nearly impossible.

- The Information Asymmetry: The civil judge does not have the same unhindered, direct access to the intelligence systems that the CTIVD has. While the judge can request documents, the State can invoke Article 8:29 of the General Administrative Law Act to withhold them on national security grounds. The CTIVD is an expert body with security clearance; the civil court is a generalist body that struggles with state secrets.2

- The Cost and Complexity: Forcing a citizen who has already undergone a complaints procedure to hire a lawyer and pay court fees for a second battle creates a significant barrier to justice. This bifurcated system discriminates against those without the financial means to litigate against the state.

5.3 Comparative Disadvantage: The UK Model

This deficiency is starkly highlighted when compared to the United Kingdom’s Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT). The IPT has the statutory power to award compensation.5 It acts as a “one-stop-shop”: it determines the facts, rules on the lawfulness, orders the cessation of surveillance, and orders the payment of damages in a single, binding judgment.

The Dutch Evaluatiecommissie Wiv 2017 explicitly noted this discrepancy. It highlighted that the separation of the finding of fault (CTIVD) and the awarding of damages (Civil Court) weakens the position of the complainant compared to jurisdictions with integrated tribunals.13

6. The Judicial Deficit: The Absence of Appellate Review

The second major structural flaw regarding the Smedema Affair is the lack of an appeal mechanism against the CTIVD’s complaints decisions.

6.1 Finality without Judicial Scrutiny

Under the Wiv 2017, the decision of the Complaints Handling Department is final (onherroepelijk). There is no possibility for the complainant—or the Minister—to appeal the decision to a higher administrative court, such as the Council of State (Raad van State).1

This means that the CTIVD acts as the court of first and last instance. While the CTIVD is independent, it is an administrative body, not a judicial one. It is not a court of law within the meaning of Article 6 ECHR (Right to a Fair Trial). By denying access to a court, the Dutch system prevents the judiciary from developing case law on intelligence matters and correcting potential errors in the CTIVD’s interpretation of the law.

6.2 The “Closed Circuit” Critique

The Evaluatiecommissie Wiv 2017 (Jones-Bos Commission) was highly critical of this “closed circuit.” They argued that the rule of law demands that binding administrative decisions be subject to judicial review. The Commission explicitly recommended introducing a right of appeal to the Administrative Jurisdiction Division of the Council of State (Afdeling bestuursrechtspraak van de Raad van State).1

The absence of appeal is particularly problematic for a complainant like Smedema. If the CTIVD interprets the concept of “national security” broadly to justify the surveillance against him, he has no way to challenge that interpretation. The CTIVD becomes the sole arbiter of the meaning of the law, unchecked by the judiciary.

6.3 Inconsistency in the Legal Framework

Recent legislative developments have made this absence of appeal even more untenable. The Tijdelijke wet onderzoeken AIVD en MIVD (Temporary Cyber Act) introduced a specific appeal mechanism to the Council of State for certain binding oversight decisions regarding new cyber powers.1

This creates a bizarre legal inconsistency:

- Scenario A: A dispute over a technical cyber warrant under the Temporary Act can be appealed to the Council of State.

- Scenario B: A fundamental rights complaint by a citizen (like Smedema) under the general Wiv 2017 cannot be appealed.

This hierarchy suggests that technical disputes between the regulator and the service are more worthy of judicial attention than the fundamental rights violations of citizens. This inconsistency undermines the coherence of the legal protection system.15

7. Comparative Intelligence Oversight: Benchmarking the Netherlands

To demonstrate “how it should be changed,” it is necessary to benchmark the Dutch CTIVD against its European peers. The comparison reveals that the Netherlands lags behind in the integration of remedial powers.

Table 1: Comparative Powers of Intelligence Oversight Bodies

| Feature | Netherlands (CTIVD) | United Kingdom (IPT) | Belgium (Standing Committee I) | Norway (EOS Committee) |

| Legal Status | Administrative Committee | Specialized Court (Tribunal) | Parliamentary Committee (Collateral Judicial Power) | Parliamentary Committee |

| Binding Decisions | Yes (since 2017) | Yes | No (mostly advisory) | No (advisory/censure) |

| Power to Stop Ops | Yes | Yes (Quash Warrant) | No | No |

| Power to Delete Data | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Financial Damages | No (Civil Court only) | Yes (Statutory Power) | No | No |

| Judicial Appeal | No | Yes (to Court of Appeal on points of law) | N/A | N/A |

| Declassification | No | Limited (Gisting) | No | No |

7.1 The UK Model as the Gold Standard

The United Kingdom’s Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) stands out as the most robust model for individual redress. Unlike the CTIVD, the IPT is a court of record. Its members are senior judges and lawyers. Because it is a court, it has the inherent power to determine civil liability and award damages.

The IPT recently evolved further. Following the Privacy International case, decisions of the IPT are now subject to appeal on points of law to the Court of Appeal. This ensures that the IPT does not operate in a vacuum but is integrated into the general legal system.

The Dutch system, by contrast, attempts to achieve “binding” oversight through an administrative committee structure without the accompanying judicial powers of compensation and appeal. This hybrid model captures the worst of both worlds: the finality of a court without the remedial toolkit of a court.

7.2 The French CNCTR Model

France offers another relevant comparison. The Commission nationale de contrôle des techniques de renseignement (CNCTR) has extensive ex-ante and ex-post powers. However, for complaints, France utilizes a specialized formation of the Council of State (Conseil d’État). The CNCTR investigates, but the final adjudication and remedy can be escalated to the highest administrative court. This aligns with the recommendation of the Dutch Jones-Bos Commission: integrating the oversight body with the supreme administrative court to ensure robust judicial protection.15

8. ECHR Compliance and International Human Rights Obligations

The ultimate legal yardstick for the Dutch system is the European Convention on Human Rights. The question is whether the CTIVD’s current powers satisfy Article 13 (Right to an Effective Remedy) in conjunction with Article 8 (Right to Privacy).

8.1 The “Big Brother Watch” Criteria

In Big Brother Watch and Others v. the United Kingdom (2021), the ECtHR refined the criteria for lawful surveillance regimes. While the Court found the UK regime largely compliant, it emphasized the importance of robust ex-post oversight that can provide “effective redress.”

The Court specifically highlighted the IPT’s ability to award compensation as a key factor in its effectiveness.10 By implication, a system that lacks this power may be vulnerable to challenge.

8.2 The “Centrum för Rättvisa” Warning

In the parallel case of Centrum för Rättvisa v. Sweden, the Court scrutinized the Swedish oversight system. It found that while the Swedish Data Protection Authority could order corrections, the lack of an effective remedy for the individual regarding the secret measures themselves was a concern.

Applying this jurisprudence to the Netherlands: The CTIVD’s inability to award damages creates a “remedy gap.” While the Dutch government argues that the combination of the CTIVD and the Civil Court satisfies Article 13, the ECtHR looks at the practical effectiveness. If the procedural hurdles of the civil court (cost, secrecy, burden of proof) make obtaining damages practically impossible for a regular citizen like Smedema, then the remedy is theoretical, not effective.

8.3 The Transparency Dilemma

The ECtHR also emphasizes that the individual should be notified of surveillance as soon as it can be done without jeopardizing the operation. The Dutch Wiv 2017 has a notification requirement (notificatieplicht), but it is riddled with exceptions and is often delayed by years or indefinitely deferred.6 The CTIVD reviews the decision to defer notification, but it cannot unilaterally order declassification or notification against the Minister’s will in all cases. This lack of transparency further degrades the effectiveness of the remedy, as the citizen cannot claim damages for a violation they are not officially aware of.

9. Future Horizons: The Temporary Act and Proposed Reforms

The Dutch oversight landscape is currently in a state of flux. The Tijdelijke wet (Temporary Act) passed to address cyber threats has inadvertently highlighted the flaws in the permanent system.

9.1 The Precedent of the Temporary Act

By allowing appeals to the Council of State for specific cyber oversight decisions, the legislature has admitted that:

- The Council of State is capable of handling secret intelligence cases.

- Binding oversight decisions should be appealable.

This sets a powerful precedent. There is no logical reason why this protection should be restricted to technical cyber disputes and denied to individual human rights complaints. The “Smedema” class of complaints deserves the same judicial protection as the “Cable Interception” class of disputes.

9.2 The “Hoofdlijnennotitie” and Upcoming Revisions

The government is currently preparing a major revision of the Wiv 2017. In the Hoofdlijnennotitie (Outline Note) for this revision, the Ministers have acknowledged the recommendations of the Jones-Bos Commission but have been hesitant to fully embrace the judicialization of complaints.16 The hesitation stems from a fear of “juridification” slowing down intelligence work.

However, “slowness” is not a valid argument against fundamental rights protection. The Smedema Affair demonstrates that without a robust, decisive, and compensatory legal mechanism, complaints can fester for decades, damaging trust in the government and leaving citizens with a profound sense of injustice.

10. Conclusion and Recommendations

The legal power of the Dutch CTIVD regarding the Hans Smedema Affair is characterized by a “halfway house” architecture. The Wiv 2017 successfully moved the system from the toothless advisory model of the Wiv 2002 to a binding administrative model. It empowered the CTIVD to say “Stop.” However, it failed to empower the CTIVD to say “Repair.”

What is “wrong” is the systemic decoupling of the finding of unlawfulness from the provision of redress. The current system forces the victim of state surveillance into a bifurcated legal process—administrative complaint for the facts, civil court for the money—that is inefficient, opaque, and practically inaccessible for the average citizen. Furthermore, the absence of judicial appeal insulates the CTIVD from the corrective scrutiny of the courts, creating a closed circuit of interpretation.

To remedy these deficiencies and ensure full compliance with the spirit of Article 13 ECHR, the following changes must be implemented:

Recommendation 1: Statutory Power to Award Damages

The Wiv 2017 must be amended to grant the CTIVD Complaints Handling Department the explicit power to award financial compensation (schadevergoeding).

- Mechanism: Adopt a provision similar to the UK’s Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, allowing the CTIVD to award compensation for non-pecuniary damage (distress) and pecuniary loss directly in its binding decision.

- Benefit: Creates a “one-stop-shop” for justice, reduces the burden on civil courts, and ensures the remedy is accessible.

Recommendation 2: Right of Appeal to the Council of State

The law must provide a right of appeal against the binding decisions of the CTIVD Complaints Department to the Administrative Jurisdiction Division of the Council of State.

- Mechanism: Expand the appeal jurisdiction currently established in the Temporary Cyber Act to cover all complaints under the Wiv 2017.

- Benefit: Ensures judicial oversight, legal consistency, and compliance with Article 6 ECHR.

Recommendation 3: Mandatory “Gisting” and Disclosure

The powers of the CTIVD should be expanded to include a mandate to provide a “gist” or summary of the reasons for the decision to the complainant, subject to strict necessity tests.

- Mechanism: Introduce a statutory duty to maximize disclosure, allowing the CTIVD to declassify summaries of facts that substantiate the finding of lawfulness or unlawfulness.

- Benefit: Reduces the “black box” effect and improves the procedural fairness of the hearing.

Recommendation 4: Legal Aid and Special Advocates

To address the inequality of arms, the state should fund a pool of security-cleared lawyers (“Special Advocates”) available to represent complainants in closed sessions of the CTIVD and the Council of State.

- Mechanism: Establish a legal aid fund specifically for Wiv complaints, ensuring that citizens like Smedema have professional representation capable of navigating the classified environment.

Only by transforming the CTIVD from a “compliance monitor” into a fully-fledged “remedial tribunal” can the Netherlands claim to offer an effective remedy for the digital age. The Hans Smedema Affair is not just a story of one man’s grievance; it is a structural indictment of a system that prioritizes the secrecy of the state over the redress of the citizen. The Wiv 2017 started the reform; the next revision must finish it.

Works cited

- Voorlichting betreffende positie klachtbehandeling in stelsel Wiv. – Raad van State, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.raadvanstate.nl/adviezen/@150139/w04-25-00101/

- Evaluatie Wet op de inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten 2002 – AIVD, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.aivd.nl/binaries/aivd_nl/documenten/rapporten/2013/12/02/rapport-commissie-dessens-met-evaluatie-wiv-2002/20131202+Evaluatierapport+commissie+Dessens+over+Wiv+2002.pdf

- Klachtenprocedure – CTIVD, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.ctivd.nl/klachtbehandeling/klachtenprocedure

- About the CTIVD | Dutch Review Committee on the Intelligence and Security Services, accessed January 1, 2026, https://english.ctivd.nl/about-ctivd

- 6. What are the national oversight mechanisms in place in your country for the activities of the security services (are they judicial, parliamentary, executive, or expert)? Do these bodies have (binding) remedial powers? – Venice Commission of the Council of Europe, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.venice.coe.int/files/Spyware//T08-E.htm

- Netherlands – SNV – intelligence-oversight.org, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.intelligence-oversight.org/countries/netherlands/

- Accountability and oversight in the Dutch intelligence and security domains in the digital age – Frontiers, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/political-science/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1383026/full

- accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.venice.coe.int/files/Spyware/NED-E.htm

- ‘Clear vision missing in oversight on Dutch secret services’ | Radboud University, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.ru.nl/en/research/research-news/clear-vision-missing-in-oversight-on-dutch-secret-services

- Recente uitspraken van het EHRM en de totstandkoming van Conventie 108+ in relatie tot het stelsel van toezicht op inlichtingen – Eerste Kamer, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.eerstekamer.nl/overig/20220224/recente_uitspraken_van_het_ehrm_en_2/document

- Ten standards for oversight and transparency of national intelligence services – IVIR, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.ivir.nl/publicaties/download/1591.pdf

- Democratic and efective oversight of national security services – https: //rm. coe. int, accessed January 1, 2026, https://rm.coe.int/16806daadb

- Recente uitspraken van het EHRM en de totstandkoming van Conventie 108+ in relatie tot het stelsel van toezicht op inlichtingen- – Tweede Kamer, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.tweedekamer.nl/downloads/document?id=2022D07517

- Annual Report TIB 2023, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.tib-ivd.nl/binaries/tib/documenten/jaarverslagen/2024/06/17/annual-report-tib-2023/TIB_Annual_Report_2023.pdf

- Contrafraternelle de la presse judiciaire e.a. t. Frankrijk (EHRM, 49526/15) – Over een effectief rechtsmiddel in het inlichtingendomein – Boomportaal, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.boomportaal.nl/rechtspraak/ehrc-updates/ehrc-a-2025-0028

- Hoofdlijnennotitie wijziging Wiv 2017 | Kamerstuk | Rijksoverheid.nl, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2023/09/01/hoofdlijnennotitie-wijziging-wiv-2017